Book Review: A Random Walk Down Wall Street

_(Note: this review originally appeared on a sister-site I’m building out, Top Financial Advisor, but I’m cross-posting it for readers here, as part of my ongoing book reviews. The last post in this series was the Advertising Secrets of the Written Word review and summary.)_

_(Note: this review originally appeared on a sister-site I’m building out, Top Financial Advisor, but I’m cross-posting it for readers here, as part of my ongoing book reviews. The last post in this series was the Advertising Secrets of the Written Word review and summary.)_

Ah, money. It doesn’t taste good. It doesn’t smell good. It can’t keep you warm at night, and it won’t love you back.

But you can trade it for something that does.

And the most remarkable thing that you can buy with money? More money. Like some sort of broken genie that allows you to wish for more wishes.

Guy at counter: Yeah, uh, I’d like to buy three dollars.

Cashier: Okay, sir, your total comes to two dollars.

Except there’s a catch, and that’s time — you can put in money and get more money out, but you’ll have to wait a while. Like growing a chia pet, instead of water, just add time.

Today’s book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street is about investing: how to find the best risk-reward tradeoff to turn your money into more money. How to buy three dollars with two.

What the book is about

The book is about random walk theory. The author defines a random walk this way: “A random walk is one in which future steps or directions cannot be predicted on the basis of past history.”

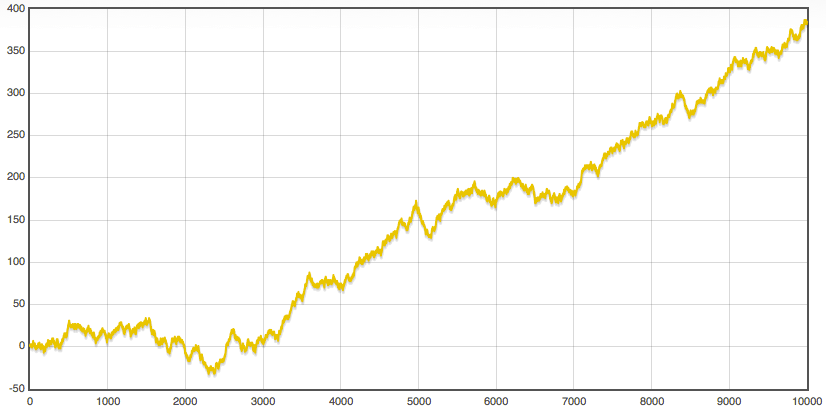

Here’s another way to think about it: imagine that you flip a coin 10,000 times. Starting from zero, with each heads, you add 1. For tails, subtract 1.

Then, plot this number against the number of flips.

Except this is 2014 and I definitely do not have the wherewithal to flip a coin 10,000 times, so I wrote a program to simulate it, and here’s what it produced:

Remind you of anything?

It looks like a stock market chart, and it sure looks like there is a trend there — you should get in on this when it starts to go up, because there is some momentum. When it goes up, it keeps going up.

Or, at least, that’s the lie your mind constructs. At any point, the next point is decided at random, by a coin flip. There’s no tradeable information in this chart at any time, by construction.

The stock market, the author argues, works in the same way. Whenever you buy an individual stock, you’re betting that the coin will land on heads.

The implication, then, is that an investor ought to buy index funds, because they allow to an investor to gain broad diversification for very cheap. (An index fund is like buying a small slice of each stock.) This diversification increases returns and decreases risk — a point which I plan on addressing in the future, because it’s sorta neat.

In theory, one could gain that diversification by constructing a portfolio from scratch — out of individual stocks, bonds, etc but, in practice, you’ll end up paying a huge premium in fees. This premium compounds over time (less money is initially invested) and can add up to staggering amounts in the long run.

Like I calculated before, a 1% increase in portfolio returns (by avoiding unnecessary costs) could be worth a quarter or a million dollars or more.

The book also has a history of speculation, discusses the correlation between risk and reward, the benefits of diversification, and how you ought to invest at different ages and under varying circumstances. Plus some example portfolios.

My opinion of the book

Price is what you pay; value is what you get. —Warren Buffet

First, I’ll tell you what I didn’t like. Then, I’ll tell you what I did.

Negatives

So, the most annoying bit of the book is the lack of technical details. I’ve seen some reviews that have described the book as either 1) too technical or 2) having enough technical meat to satisfy engineers.

Nope. Graphs were seen but, in general, little technical explanation beyond the standard economic just-so stories. (If anyone has ever told you that raising minimum wage is bad “because supply and demand,” you’ve encountered an economic just-so story. In reality, economists are split on the issue.)

Further, the book uses what is the most annoying rhetorical trick of all time. It goes like this. The author has a theory. They say something like, “There is a moon-sized pile of evidence that supports my theory.”

And then they cite none of it.

Here is a real example: Billionaire Seth Klarman has written a paper, in which he argues that markets are like so inefficient, duh, and that “armchair academics … cling to their theories even in the face of strong evidence that they are wrong. ”

Annnnnd, the paper continues and no strong evidence is seen. WHERE IS THE EVIDENCE, KLARMAN? SHOW ME THIS STRONG EVIDENCE.

To prove that the moon exists, just point.

This is probably not a big deal to most readers but, as disgruntled blogger planning on digging deeper into the available literature, it was pretty fucking annoying.

Beyond this, I would describe the prose as good for an economist but nothing that impressive. An unmotivated reader may have trouble getting through it.

The humor is also pretty weak.

Positives

Okay, with that unpleasantness out of the way, on the whole, I thought the book was very impressive. Indeed, I was most taken with the just how reasonable the author’s opinions and statements were.

I’d expected an ideological barrage about market efficiency, but instead I found a very measured message — along the lines of, “Markets are weakly efficient, such that it’s unlikely that an individual investor can beat the market. But I understand the urge, and if you want to pick individual stocks, here are some guidelines.”

The book doesn’t even argue for the strong or semi-strong versions of the efficient markets hypothesis (EMH), instead conceding that it’s not a perfect random walk, and that there is some momentum — just not enough that someone can trade on it and still beat the market after taking into account fees, and taxes, and all the things that make people say, “Life forever? I don’t want to live forever.”

All the weak EMH requires is that “market participants not be able to systematically profit from market ‘inefficiencies’.” This doesn’t seem absurd to me, but I’m not yet convinced of. There certainly seems to be at least one person who’s returns are not explained by chance. (Spoilers: it’s Warren Buffet.)

And it seems a little galling that aggregating the bets of irrational market participants (ala behavioral finance) should result in rational prices, and don’t give me that law of large numbers “explanation.”

But I’m planning on surveying a lot more related evidence, so I haven’t come to any strong opinions either way yet.

Beyond that, the book is an absurd value (as are a lot of resources when it comes to money.) You can buy a copy for like 11 bucks off of Amazon and, by using the advice contained therein, realize probably an extra 1% in annual returns, which adds up to tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars over a lifetime.

So it’s sorta like trading 11 dollars for 250,000 dollars in the future.

What I’m saying is: this book on investing is a good investment. You should buy a copy.