Analogical Thinking: Concepts as Example Bundles

Analogy is our best guide in all philosophical investigations; and all discoveries, which were not made by mere accident, have been made by the help of it.

—Joseph Priestley

Words are not the stuff of thought.

This is straightforward to demonstrate. Present someone with a quote — it can be anything, but for concreteness let’s say you go with a bit of Thoreau: “I was not designed to be forced. I will breathe after my own fashion. Let us see who is the strongest.”

So, you present this line to someone, and then you let some time pass, say an hour. Then, ask them to repeat the quote back to you. What do they tell you?

I’d wager that you don’t get the exact quote back, but the gist of the thing. Sort of like when reading this, you will come away not with an exact memory of each word and every comma, but instead a general idea of what it is that I’m talking about — a summary. Almost as if your mind were a lossy compression algorithm.

If words were the stuff of thought, or at least of memory, you’d expect the mind to store words as, well, words. If words were the stuff of thought, when presented with a quote, on recall you’d repeat the exact quote back.

But, instead, there seems to be some kind of mental translation that goes on. You don’t remember the exact quote but, instead, it gets stored as a “gist,” as if your mind translated it to meaningness.

So, words are not the stuff of thought.

Let me put it another way. What I’m saying is that, when you are offered some concept in words, you store that concept in meaning-nese. And, then, when you communicate it with someone, you translate that meaning-nese back into words.

This explains why the quotes are not exact, but become garbled — the words have to undergo translation: first, from words to meaning-nese to be stored, and then from meaning-nese back into words during recall. It’s like taking English, translating it into Chinese, and then translating it back into English.

You won’t end up with the original English.

How this relates to metaphor

Analogy is anything but a bitty blip — rather, it’s the very blue that fills the whole sky of cognition — analogy is everything, or very nearly so, in my view.

—Doug Hofstadter

Now, with this in mind, let’s consider the problem of communication. To make this easier, let’s restrict ourselves to idealized communication — comminucation where the goal really is communication. This is different from communication “in the wild”, where a lot of talking is not about substance, but about expressing friendliness or (perhaps unconsciously!) furthering one’s agenda.

So, idealized communication, where discussion really is about the transfer of ideas. Given this idea of meaningness translation, what can we say about this transfer?

Well, the goal of communication is for the speaker to translate some useful structure she has in her mind, encoded in meaning-nese, and to re-encode it in some other form — typically language, but it could also be art, or movement, whatever.

Then, the task of the listener, is to take this language-encoded structure and to decode it back into the original meaning-nese — or, at least, some dialect of meaning-nese compatible with the listener’s mind.

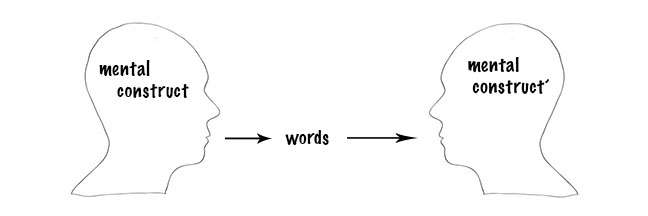

Thus, communication is really about the transfer of useful mind structures between speakers — but, since we can’t directly transfer from one brain to another via an uplink ala The Matrix, there’s an intermediate encoding and decoding step.

Visually:

What labels imply

Okay, let’s take a step back then and consider the implications. What does it mean when you encounter a word or a phrase that you don’t understand? What does that indicate?

If we take the encode-decode dance literally, it’s an indication that the speaker has some useful cognitive structure in her head, with which you’re unfamiliar. So, concretely, I recently learned the word “ostensibly” which means “as it seems on the surface, but perhaps not actually.”

I have found this a gratifying label to have in my head, now that I’ve gone through the effort of re-building the cognitive structure that it represents. I can say something like, “Big business is ostensibly pro-immigration reform because they care about the welfare of would-be immigrants.” And “ostensibly” here acts as a sort of wink that says, yeah, that’s one explanation, but maybe there’s something more to it. In this example, this something more would be that maybe business just cares about cheap labor.

So, what am I trying to say here? What’s the practical interpretation? When you come across some equation, word, phrase, or whatever, that strikes you as foreign, this signals that the person has some useful cognitive structure that you don’t.

What does this have to do with analogy

Now, in a section that is about analogical thinking, you are maybe wondering why I’ve taken you through this detour into communication and cognitive structures. The idea is that, in some sense, all language acts as a metaphor.

This notion has recently been making the rounds with the endorsement of Doug Hofstadter, of Gödel, Escher, Bach (very recommended) fame, but the idea is at least as old as Lakoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (and, no doubt, older still than that.)

Here is what I mean when I say that all communication is analogy. Consider again the encode-decode theory I just told you about: it’s about taking meaning-nese, mapping it into words, and then unmapping it back into meaning-nese.

What do you call a mapping between two different things? An analogy. So, in a sense, all communication is about constructing an analogy between cognitive structures and words, and then the task of the listeners is to decode that analogy into their own mental model.

Essentially, that’s what’s happening right now: I’m encoding my ideas here, as words, and you, the reader, are decoding them. And, if everything is going as planned, you’re building a cognitive structure in your head right now which is similar to the one that I have in mind.

This is what separates a good exposition from a bad one: with a good one, it’s easy to decode and build up the writer’s cognitive structures in your own mind. With bad exposition, you either end up with no structure or a damaged one, a misunderstanding.

Concepts as analogical bundles

In fact, we can go even a little further than this, and say, what is a concept, really? That is, what are these cognitive structures that I have in my mind?

As a concrete example, let’s consider the number three. What is the idea of three-ness?

Well, with the concept, if you wanted to transfer it to a young child, you’d give concrete examples. A group of three rocks, three bananas, and so on, except of course you wouldn’t say “three” — you would show them three rocks, three bananas, and you’d ask them, so, what do these things have in common?

With enough examples, they would catch on, or at least so I suspect. I’ve been unable to acquire the necessary funding to experiment on young children.

The idea, though, is that with any concept, when you start unbundling it, you find that it’s really just a bunch of examples with some common core — some hidden structure, that isn’t immediately obvious when you consider just one thing in isolation, but becomes apparent with the study of tangible examples.

That is, a concept is a bundle of examples. The process of abstraction, of obtaining a useful cognitive structure, is ultimately one of comparing and contrasting these examples, until have built up this structure in your mind.

Some evidence regarding analogical thinking

So, let’s recap for a moment:

- Communication is the process of translating a cognitive structure into words, and then from words back into a cognitive structure.

- This mapping and unmapping is an analogy: setting up an isomorphism between cognitive structures and words.

- A concept is a bundle of concrete examples. Each example contains some common core, with is captured in the concept. Thus, every concept is itself an analogy.

So, really, here we have two different uses of analogy: a concept/cognitive

structure is an analogy, and we use a process of analogy to transfer them

between people.

If this is really true, if I’m not just spinning you a nice story, we ought to expect that the study of concrete examples is the best way to go about learning a new concept. Really, it’s probably the only way to build a new cognitive castle in your head.

Is there any evidence to support this view? Well, yes. There’s significant evidence suggesting that comparing and contrasting examples is a powerful technique when it comes to understanding something new.

Consider the inert knowledge problem. This is when you’re in a situation, and you have relevant, applicable knowledge, but you fail to apply that knowledge. So, concretely, say you’ve taken a basic calculus class, and you’re arguing with someone about population growth. You get in this heated disagreement. They say that our current growth is unsustainable, and we’re headed towards an inevitable collapse because there is not enough food to go around — a Malthusian catastrophe.

You take a contrary position, and point out that, as nations develop, birth rates fall, such that population growth is below the replacement rate in some developed nations, like Japan and Germany. At a certain tipping point of prosperity, population plateaus and then actually begins to fall.

If your calculus knowledge transferred, here you might realize that this is an argument about the shape of the derivative of population growth. And, if you so realized, you might both draw out curves of what you think it looks like, and then compare that to real-world data.

The inert knowledge problem would be 1) knowing calculus, 2) having this argument, and 3) not realizing that you’re actually arguing about derivatives.

Now, depending on the amount of learning you’ve done in the past, you may or may not have noticed that inert knowledge is the devil. Why learn something if you fail to apply it? What can be done about this?

Well, okay, learning something is about the acquisition of concepts, right? So calculus knowledge is about building up calculus structures in your head.

If, as I’ve argued, this is the case, we might expect that comparing and contrasting examples (and thusly promoting concept acquisition) would help us overcome the inert knowledge problem.

Is this the case?

Yes. There’s even some evidence that comparing and contrasting examples, “analogical encoding”, is potentially the only effective technique at dealing with this inert knowledge plague. One review put it this way: “The best-established way of promoting relational transfer is for the learner to compare analogous examples during learning (Catrambone & Holyoak, 1989; Gentner, Loewenstein, & Thompson, 2003; Gick & Holyoak, 1983; Reeves & Weisberg, 1994; Ross & Kennedy, 1990; Seifert et al., 1986, Experiments 1 and 2).”

The quoted study further finds that analogical encoding — comparing and contrasting examples — not only promotes future transfer, but actually works backwards, too.

What do I mean by this? I mean that, if you sit down and compare and contrast examples, you’re going to be much more effective at coming up with past, relevant experiences of the principle in question. You can use this to transform inert knowledge into animated knowledge. To piece together the once dead into a new Frankenstein’s monster.

To use our calculus example again, if you’re reading about the jerk (the rate of change in acceleration), and you compare and contrast real-world examples, you’re more likely to spontaneously realize that, when learning to drive, the jerk you felt when stopping too quickly was an example of, you know, the jerk in physics.

Benefits for the acquisition of expertise

So, at this point, I hope you’re convinced that comparing and contrasting examples is the way to go about acquiring a new concept — it’s how to absorb a bundle of concrete examples and distill them into a useful cognitive structure.

But that’s not all! This is not the only benefit. Consider what it means to be an expert at something. One of the most cited studies on expertise compared how graduate students in physics categorized physics problems, versus how novices did.

The finding? Physics experts were more likely to pick out the underlying physical principle, while novices tended to focus on irrelevant surface characteristics. Presumably, physics experts had built up a cognitive structure that they recognized in the problem. The novices, lacking this mental structure, were unable to spot it.

If the theory I have sketched here is correct, then we ought to expect that comparing and contrasting examples will accelerate the acquisition of concepts and therefore expertise. Analogical encoding allows one to swim out from shallow seas and into the depths — “comparison between two analogous examples acts to make their common relational structure more salient (Gentner & Medina, 1998; Gentner & Namy, 1999; Markman & Gentner, 1993).”

Practical implications

Okay, then, we’ve just breezed through the core ideas of analogical thinking. To sum it up:

- Words are not the stuff of thought. Our minds translate words into something else (meaning-nese).

- Communication is essentially about analogy: it’s about mapping a cognitive structure (“meaning-nese”) into words, and then the listener unpacks that back into a cognitive structure.

- Thus, successful communication is about setting up understandable analogies.

Then, I covered the relationship between concepts and analogy:

- A concept is a bundle of concrete examples that illustrate some core relationship between those examples. The concept of three-ness can be understood as the relation between concrete instances of three things (bananas, rocks, years).

- Given that a concept is a bundle of examples, we should expect that the best way to acquire a useful cognitive structure is to compare and contrast examples (“analogical encoding”).

- There is a significant body of evidence that suggests that this is the case: comparing and contrasting examples is a powerful way to acquire a concept.

I also touched on the inert knowledge problem, and how analogical encoding

allows us to overcome it:

- The inert knowledge problem is when you have relevant knowledge but fail to take advantage of it. Example: failing to realize that an argument about population growth is an argument about the shape of a derivative.

- The only consistently supported method of overcoming the inert knowledge problem, and promoting the application of a concept in new situations (“transfer”), is analogical encoding — by comparing and contrasting examples. “When subjects explicitly compared the analogs and then immediately attempted to solve the target problem in the context of a single experiment, transfer was obtained with significant frequency even without a hint that the analogs and target were related. (Holyoak and Catrambone)”

Finally, I mentioned how this relates to expertise:

- Experts are distinguished by better developed cognitive structures. Physics experts, for example, are able to pick up on the underlying structure of physics problem, while novices focus on surface characteristics.

- How can we acquire such a cognitive structure? By analogical encoding — comparing and contrasting examples. Contrasting examples fosters a focus on deeper structures.

- Thus, to accelerate the acquisition of expertise, one should take advantage of analogical encoding.

So, practically speaking, how can you, as an individual put this into practice? This method, analogical encoding, is both simple and powerful. To acquire a new cognitive structure, gather together a bunch of examples of the concept, and then compare and contrast those examples.

If you would like to improve your calculus skill, you should Google for real-world examples of derivatives or integrals or any concept that you’d like to acquire. Then, write them down, and then list how each is similar and each is different.

You can also use these principles to improve your communication and teaching skills. If you want someone to obtain a cognitive structure that you have, illustrate the principle with examples, and then bring their attention to the underlying similarity connecting the examples. In the case of this section, the principle behind all of these examples has been that learning and communication is about the transfer of concepts, which are bundles of examples, and can be acquired by contrasting concrete examples.

Now, what was that Thoreau quote, again?

Further Reading

- If you enjoyed this, check out a copy of Metaphors We Live By, Surfaces and Essences, or “Analogy as the core of cognition.”

- This is far from the first time that I’ve written about learning and expertise. Check out my articles on the science of problem solving, the importance of “why?” questions, compressing knowledge, and the role of memory in human expertise. Oh, and if you just want to enjoy a metaphor, none of mine have resonated more with the internet at large than online communities as vampire bat colonies.