Creativity, Fan Fiction, and Compression

I’ve written before about the relationship between creativity and compressibility. To recap, a creative work is one that violates expectations, while a compressible statement is one that’s expected.

For instance, consider two sentences:

- Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

- Where there’s a will, there’s a family fighting over it.

I suspect you find the second more creative.

Three more examples of creative sentences:

- When I was a kid, my parents moved a lot. But I always found them.

- Dad always said laughter is the best medicine, which is why several of us died of tuberculosis.

- A girl phoned me the other day and said, “Come on over, there’s nobody home.” I went over. Nobody was home.

Given that less predictable sentences are more creative, and less predictable sentences are less compressible, creative works ought to be less compressible than non-creative ones. And, indeed, I found some evidence for this in a previous experiment.

But that was not too compelling as it compared technical, repetitive works to novels. This time, I decided to compare very creative writing to normal creative writing.

Methods

The idea then is to compare the compressibility of amateur creative writing with that of experts. To accomplish this, I took 95 of the top 100 most downloaded works from Project Gutenberg. I figure that these count as very creative works given that they’re still popular now, ~100 years later. For amateur writing, I downloaded 107 fanfiction novels listed as “extraordinary” from fanfiction.net.

I then selected the strongest open source text compression algorithm, as ranked by Matt Mahoney’s compression benchmark — paq8pxd. I ran each work through the strongest level of compression, and then compared the ratio of compressed to uncompressed space for each work.

Analysis and Results

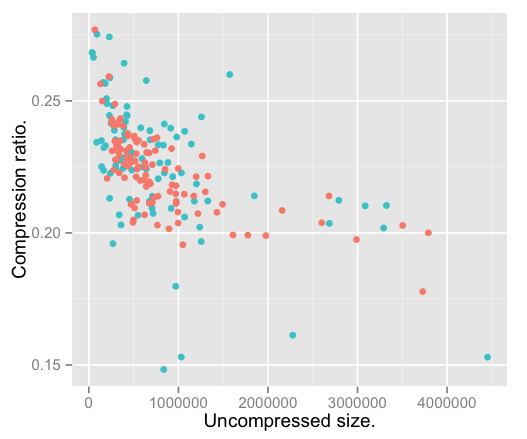

I plotted the data and examined the outliers, which turned out to be compressed files that my script incorrectly grabbed from Project Gutenberg. I removed these from the analysis, and produced this:

Here the red dots are fanfiction novels, while the blue-ish ones are classic works of literature. If the hypothesis were true, we’d expect them to fall into distinct clusters. They don’t.

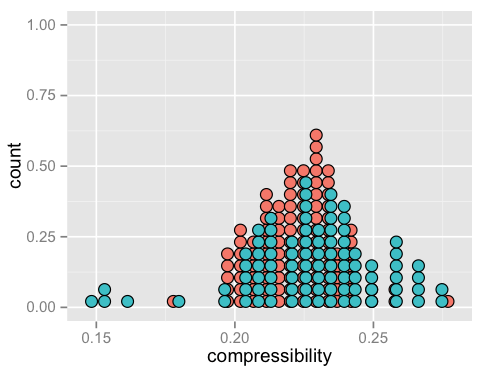

Comparing compressibility alone produces this:

Again, no clear grouping.

Finally, I applied a Student’s t test to the data, which should tell us if the two data sets are distinguishable mathematically. Based on the graphs, intuition says it won’t, and indeed it doesn’t:

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: dat$RATIO by dat$CLASS

t = -1.3614, df = 144.26, p-value = 0.1755

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.009924785 0.001828882

sample estimates:

mean in group FANFIC mean in group LITERATURE

0.2230189 0.2270668

The p-value here is 0.1755, which is not statistical significance. The code and data necessary to reproduce this are available on GitHub.

Discussion

I must admit a certain amount of disappointment that we weren’t able to distinguish between literature and fanfiction by compressiblity. That would have been pretty neat.

So, what does this failure mean? There at least six hypothesis that get a boost based on this evidence:

- Creativity and compression are unrelated.

- A view of humans as compressors is wrong.

- Human compression algorithms (the mind) and machine compression algorithms are distinct to the point where one cannot act as a proxy for the other.

- Compression algorithms are still too crude to detect subtle differences.

- Fanfiction is as creative as literature.

And so on and, of course, it’s possible that I messed up the analysis somewhere.

Of all of these, my preferred explanation is that compression technology (and hardware) are not yet good enough. Consider, again, the difference between a creative and a not-creative sentence:

- Honesty is the best policy.

I want to die peacefully in my sleep, like my grandfather… not screaming and

yelling like the passengers in his car.

The first is boring, right? Why? Because we’ve heard it before. It’s compressible — but how’s a compression algorithm supposed to know that? Well, maybe if we trained it on a corpus of the English language, gave it the sort of experience that we have, then it might be able to identify a cliche.

But that’s not how compression works right now. I mean, sure, some have certain models of language, but nothing approaching the memory that a human has, which is where “human as computer compression algorithm” breaks down. Even with the right algorithm — maybe we already know it — the hardware isn’t there.

Scientific American estimates that the brain has a storage capacity of about 2.5 petabytes, which is sort of hand-wavy and I’d bet on the high side, but every estimate I’ve seen puts the brain at more than 4 gigabytes, by at least a couple orders of magnitude. I don’t know of any compressors that use memory anywhere near that, and certainly none that use anything like 2.5 petabytes. At the very least, we’re limited by hardware here.

But don’t just listen to me. Make up your own mind.

Further Reading

- The idea that kicked off this whole line of inquiry is Jürgen Schmidhuber’s theory of creativity, whichI’ve written up. If you prefer, here’s the man himself giving a talk on the subject.

- To reproduce what I’ve done here, everything is on GitHub. That repository is also a good place to download the top 100 Gutenberg novels in text form, as rate-limiting makes scraping them a multi-day affair.

- I similarly compared technical writing and creative writing in this post and did find that technical writing was more compressible.

- For an introduction to data compression algorithms, try this video.

- Check out the Hutter Prize, which emphasizes the connection between progress in compression and artificial intelligence.

- For a ranking of compressors, try Matt Mahoney’s large text compression benchmark. He’s also written a data compression tutorial.