Creativity, Literature, and Compression

But first, a joke:

I was at a bar last weekend, chatting with this woman. She was decent looking. There was a lull in the conversation, so I say to her, “Hey, I’ve got this talent. I can tell when a woman was born after feeling her breasts.” She doesn’t believe me at first, but after a minute or so, she comes around. “Go on, then,” she says to me. I feel her up a bit before she gets impatient. “Well, when I was born?” she asks. So I tell her — “Yesterday.”

Dissecting and killing the joke

What’s funny about that joke? The surprise. First, there’s the set up. It’s titillating, and listeners start anticipating: this is going somewhere. And then — punchline! Outta nowhere, or at least that’s what it feels like. Cue laughter. This shock, this violation of expectation, is what comedy’s all about.

Here’s another one: “I’m not a member of any organized religion. I’m a Jew.” If the sentence had instead been, “I’m not a member of any organized religion. I’m an atheist,” there would be nothing at all funny about it. George Carlin’s, “If you can’t beat them, arrange to have them beaten,” follows the same pattern.

Brains are sort of anticipation engines and, when you violate those expectations, well, that’s comedy. It’s the difference between something original and something not. If Carlin had said, “If you can’t beat them, join them,” I wouldn’t be talking about him. It’s boring, cliched. It’s not creative.

Creativity is about violating expectations.

Anticipation is compression

Anticipation and prediction are the same thing. When I drop a ball, I anticipate and predict that it will fall to the ground.

Now, let us imagine a program that can take in a few facts about you and then predict with certainty what it is that you’re going to say. In such a case, the machine wouldn’t need to remember anything about you except those few facts. If it needs to know your opinion on something in the future, it can take those facts, run them through its internal predictor, and regenerate your opinions.

You, as a human, sort of already do this. For instance, if I tell you how I lean politically, you might not need to know my stance on anything — you might be able to anticipate it. So instead of storing, “The author’s opinion on Serious Political Topic X,” in long term memory, you could just remember, “The author is a Blue.”

This difference between remembering everything and remembering just a few details is compression. It follows, then, that when you can predict something, you can compress it.

Given then, that:

- Creativity is about violating expectations.

- That which can be expected can be compressed.

I would expect that creative things are less compressible than non-creative things. Do creative books compress less than non-creative ones?

That’s what I want to find out.

Methods

The idea, then, is to take works that are creative and non-creative, compress both, and observe whether the non-creative books are more compressible. Given the theory fleshed out above, I expect the non-creative works to be more compressible.

Sorting books into creative and non-creative buckets is, by its nature, a subjective task. I attempted to grab from the most obviously creative and non-creative works. In practice, this tended to blur the line between non-creative and boring. The most mind-numbing works, I figure, are the least creative.

Creative works:

- Alice in Wonderland

- Godel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid

- Through the Looking Glass

- Flatland

- Beyond Good and Evil

- Emerson, First Essays

- A few other popular novels on Project Gutenberg.

Non-creative works:

- The Berne Convention

- RFC 4880

- IRS Publication 557: Tax exempt status for your organization

- ITunes User Agreement

- Patent 8,322,614, “System for processing financial transactions in a self-service library terminal”

- The Affordable Care Act

I took each of these works, ran them through the xz compressor — the strongest general purpose compressor in wide circulation, as far as I know — and then compared the “compressibility” (ratio of uncompressed to compressed data) of the two classes of files. The comparison was done with R.

Analysis and Results

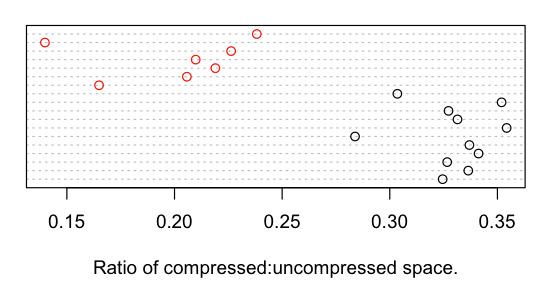

Before anything else, I plotted the compressibility of the data using a dotplot, and colored each by work as creative or not. The results are visually striking:

You will notice that the works fall into two distinct clusters. Creative works (black) are less compressible than non-creative works (red), which is what I would suspect given that my hypothesis is true.

My statistics-fu is weak, but I think the Student’s t-test is the right tool for the job here. This calculates the p-value that the two groups are different, which comes out to 0.00001488 or, if the computer could speak, “I’m near certain that the non-creative group is more compressible than the creative group.” (That level of certainty is almost certainly inappropriate, though. In a trial of 10,000 analyses like these, I screw up more than one of them.)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: dat$RATIO by dat$CLASS

t = 8.7316, df = 8.58, p-value = 1.488e-05

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

0.09487109 0.16189135

sample estimates:

mean in group CREATIVE mean in group NOT_CREATIVE

0.3289321 0.2005509

Limitations

Let’s dig in a little deeper to the creative works:

> dat[c(-3,-2)]

FILE CLASS RATIO

6 creative/geb.txt CREATIVE 0.2838554

11 creative/wizard-of-oz.txt CREATIVE 0.3035146

1 creative/alice_in_wonderland.txt CREATIVE 0.3245573

3 creative/breakfast-of-champions.txt CREATIVE 0.3266665

9 creative/through_the_looking_glass.txt CREATIVE 0.3272843

8 creative/poe.txt CREATIVE 0.3314520

2 creative/beyond-good-and-evil.txt CREATIVE 0.3364589

5 creative/flatland.txt CREATIVE 0.3369884

4 creative/emerson-first-essays.txt CREATIVE 0.3412482

10 creative/ulysses.txt CREATIVE 0.3519374

7 creative/jekyll-and-hyde.txt CREATIVE 0.3542899

This is sorted from most compressible to least, implying that Jekyll and Hyde is the most creative novel of those tested, while Godel, Escher, Bach is the least. I find this unlikely.

Indeed, if I plug in Moby Dick, I get a ratio of .3353, or less compressible than Alice in Wonderland, Breakfast of Champions, and others. Now, I’ve read Moby Dick and it’s a terrible, boring affair. I much prefer Godel, Escher, Bach or Alice in Wonderland. And internet reviewers largely do, too.

So it seems that compressibility can classify novels from technical works, but it’s not — at least using xz — possible to separate very creative works from just creative works.

Discussion

So, the theory predicted that non-creative works would be more compressible than creative ones, and that panned out. This is far from confirmation of the model, but it’s still evidence, and I’m pretty confident that the average novel is less compressible than the average piece of technical work.

It would be much more impressive if this could distinguish more specific degrees of creativity. If I compared some of the novels produced by first time authors (or bad fan-fiction) to those on the Modern Library’s top picks and it found that the Modern Library picks were more creative, well, that’d be neat. (Maybe I will try this out in a future post.) We can imagine such a technique becoming more and more powerful — to the point where it can distinguish between the relative merit of different works by the same author.

The limiting factor here, of course, is the power (or intelligence) of the compression technology. The compression algorithms that we all use are not that complicated. I can feed them sensory input and they won’t compress it down to the laws of physics. Instead, they’re relatively crude-but-effective attempts at deduplication, which means that they’re an imperfect measuring sticks for how creative something seems to a human.

For instance, if I feed a compressor a cliche or a clever play on that cliche, the compressor doesn’t have the intellectual context necessary to ding the cliche. If I could, instead, train an algorithm on a huge corpus of English text, of the sort that Google possesses, I’d be able to better construct a compressor that’d evaluate originality.

Even then, there are theoretical limits on this. I could feed a compressor random input, which cannot be compressed, but that doesn’t mean that there’s anything of interest to humans. And we can wonder: how much can word alone, surface level characteristics of text, be representative of creativity? At some point, a sufficiently intelligent compressor must understand the content, too.

In that final sense, humans are the ultimate compressors — at least for now.

Further Reading

- The ideas for this project have been rattling around in my mind since I wrote about Jürgen Schmidhuber’s theory of creativity.

- Marcus Hutter is offering €50,000 to anyone who discovers one of those sufficiently advanced compressors I mentioned.

- For an introduction to compression algorithms, check out this talk that was given at Strangeloop.

- A story about what It’d be like to be a “sufficiently advanced” compressor.

- The code and data used for the analysis are available on GitHub.