Hard Books Are Overrated

Widely used calculus books must be mediocre.

— W. Rudin

I’ve noticed a phenomenon, especially in mathematics, where anyone asking for book recommendations invariably is recommended the least-gentle-but-still-reasonable textbook imaginable. A high school student might ask for an introduction to calculus and someone will tell them to read Principles of Mathematical Analysis. Looking for an introduction to programming? Hey, try Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs — or just read Knuth!

Several possible explanations spring to mind:

- By recommending a difficult book to someone, you’re signalling your own intelligence.

- Struggling against a text results in a sort of Stockholm syndrome, where one becomes more fond of it as they sink more hours into it.

- Recommending an easy book can be socially costly as the receiver might interpret it as an insult. It’s safer to recommend a hard book.

- When asked for a book recommendation, people mentally grasp the book most representative of that subject, and this leads to a bias towards not-beginner-friendly texts.

- Hard texts are that much better than anything else.

- Familiarity with a subject damages one’s ability to judge whether or not a text is appropriate for someone without the same background.

- Those recommending hard textbooks have not, generally, tried to self-study them, but rather sat through a class that required the text and completed 10% of the problems as homework.

All of these could be true, but what we really want to know is: are hard books systematically overvalued?

Comparing the utility of books

Now, I have no doubt that reading one hard book is more valuable than reading one easy book, but that’s not a fair fight. I could get through The Design of Everyday Things in a couple of days, while working through Knuth’s Concrete Mathematics would take me the better part of a year. If you accept that a book like Concrete Mathematics can take 200 hours while an easy book might take 4, the question becomes: Is one hard book worth fifty easy ones?

Microeconomics

We can consider taking this completely literally. Consider perhaps the most straightforward application of microeconomic theory ever: If two men are selling rugs, but one man is able to sell his rugs for ten times as much, well, customers are deriving more value from his rugs.

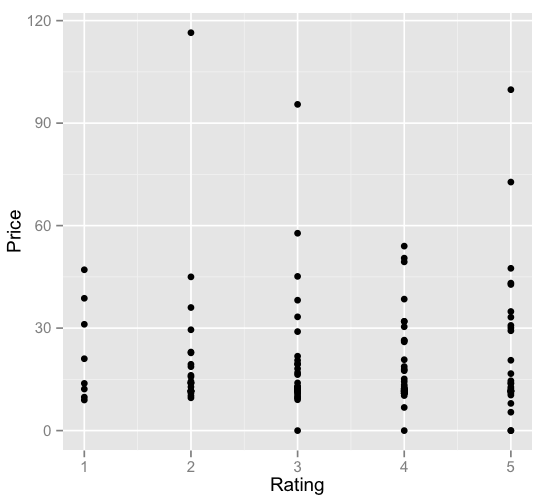

50 easy books will, most of the time, cost more than 1 hard book. We might expect, then, that 50 easy books will provide more value to the consumer. I actually have painstakingly collected statistics on my own reading, but there’s no correlation between my rating of a book and its price (alas).

A stroll through the New York Times’s best seller list also reveals no obvious relationship between how interesting a book looks and its price. A look at computer science and programming books is a bit more compelling. The obviously more valuable books (e.g. The Art of Computer Programming) are selling for more than the nth Adobe Photoshop manual.

A stroll through the New York Times’s best seller list also reveals no obvious relationship between how interesting a book looks and its price. A look at computer science and programming books is a bit more compelling. The obviously more valuable books (e.g. The Art of Computer Programming) are selling for more than the nth Adobe Photoshop manual.

So easy books win here, but it’s not clear if this win is worth anything.

Amount learned

Instead, we can take the tack of estimating the amount learned from a book. When going through The Design of Everyday Things, I learned maybe 10 things. Today, I started reading Petzold’s CODE and have taken about 50 separate notes. At this rate, I should end up with something like 300. A significant variance here, but let’s say the average easy text can teach someone 35 new things — more if you’re careful with book selection.

If I consider, on the other hand, a harder text, like Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, the amount available to learn is about an order of magnitude greater. Depending on the number of exercises one wades through, anywhere between one and three thousand seems reasonable.

This one could really go either way. A broad selection of fifty popular science texts will teach a person more than one really hard book, but one hard book will teach you more than fifty so-so spiritual or diet books.

And, of course, all learning is not created equal. Some things really are more important than others.

Possible heuristic: popular science is great for building a broad understanding, while difficult works are great for pushing one to the next level via deliberate practice.

Revealed preference

I can count the number of people I know who routinely fight their way through hard books on one hand. It’s not a normal thing that people do, even curious people. Indeed, curious people are notable for being more willing than most to read a wide variety of texts, not for the difficulty of those texts.

University courses

University professors typically assign more difficult textbooks (although often not truly difficult, a sorta middle ground.) Still, consider the popularity of a book like CLRS versus The Algorithm Design Manual. The first is more popular, the second more readable.

I’m not sure who wins this round: on the one hand, university textbooks are harder to read than what’s on the New York Times bestsellers list. On the other hand, most university courses are not requiring books like Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, instead opting for something gentler.

Plus, these medium difficulty textbooks are often little more than props for a class, something to accompany lectures and provide exercises. Still, on the whole, it seems more honest to call this a win for difficult books.

Comprehension, amount retained

On difficult texts, one Less Wrong commenter wrote this:

I found that when a text requires a second or third reading, taking a lot of notes, etc., I won’t be able to master it at the level of the material that I know well, and it won’t be retained as reliably, for example I won’t be able to re-generate most of the key constructions and theorems without looking them up a couple of years later (this applies even if more advanced topics are practiced in the meantime, as they usually don’t involve systematic review of the basics). Thus, there is a triple penalty for working on challenging material: it takes more effort and time to process, the resulting understanding is less fluent, and it gets forgotten faster and to a greater extent.

Success

If we live in a world where hard books were clearly superior to easier ones, I would expect that the reading habits of successful people would center around difficult books.

This isn’t the impression that I get, in general. CEOs fill their reading lists with biographies, not textbooks. If you looked at the reading habits of Bill Gates, you’ll see that it’s filled with popular non-fiction rather than hefty technical works.

Closing remarks

All of this suggests a heuristic: to decide what to read, ask yourself, “What’s the easiest book I could read that will teach me a lot?” Or, alternatively, “What’s the easiest book that will move me towards my goals?”

For reading broadly, popular works seem like a clear win. I think it’s best to save difficult works in a field until you’ve reached diminishing returns on easier texts. If you’re not learning much, then you ought to move onto something harder.

Ideally, the process of reading through easy texts on a subject before tackling harder ones transforms once difficult books into easy ones. This pattern of reading looks more like a slow progression than a violent struggle — small steps instead of leaps.

Further Reading

- I have touched on this topic several times before.

- For another perspective, check out Eric Drexler’s “How to Learn About Everything.”

- The idea of slowly building towards something is related to success spirals.

- If you need ideas about what to read, I track my reading and post reviews to my Goodreads account. Or there’s Bill Gates’s favorite books of 2013.