Prolonged Eye Contact and Attraction: What The Science Tells Us

Belladonna means “beautiful woman” in Italian, but it’s also the name of a type of plant. The origins of the term belladonna are uncertain, but date back to at least 1554.

It’s been suggested (and this is my favorite theory) that the name might be related to belladonna’s use as a cosmetic. Women would consume the plant in order to dilate their pupils, in an attempt to enhance beauty.

The only problem? Belladonna (sometimes called nightshade) is poisonous.

Richard Pultney’s 1757 paper, “A brief botanical and medical history of the Solanum Lethale, Bella-donna, or Deadly Nightshade,” recounts this tale:

Its relaxing quality is very surprising, as appears by that memorable case… of a lady’s applying a leaf of it to a little ulcer, suspected to be of the cancerous kind, a little below her eye, which rendered the pupil so paralytic, that it lost all its motion for some time afterward: and that this event was really owing to that application, appears from the experiment’s being repeated with the same effect three times.

But they were really onto something! This is the craziest part of the whole thing. (Suffering for fashion is passé.) Hess (1965) took two pictures of the same woman and presented it to male subjects and asked them to describe the woman

But they were really onto something! This is the craziest part of the whole thing. (Suffering for fashion is passé.) Hess (1965) took two pictures of the same woman and presented it to male subjects and asked them to describe the woman

in the picture. The researchers altered the photos so that one had slightly larger pupils. By and large, the male subjects preferred the woman with the larger pupils.

Try it:

(The one on the bottom is the one that you’re supposed to find more attractive, although I’ve just terrifically biased you by telling you that.)

This has since been replicated at least five times.

Let’s just take a minute and reflect on this. Women in 16th century Italy anticipated the findings of modern scientific research by about 400 years. They not only discovered that belladonna reliably increases pupil size, but they also noticed that men were attracted to that.

I propose a hypothesis similar to the efficient markets hypothesis. We’ll call it the efficient beauty hypothesis: if a beauty-increasing cosmetic intervention exists, some enterprising individual somewhere will discover it.

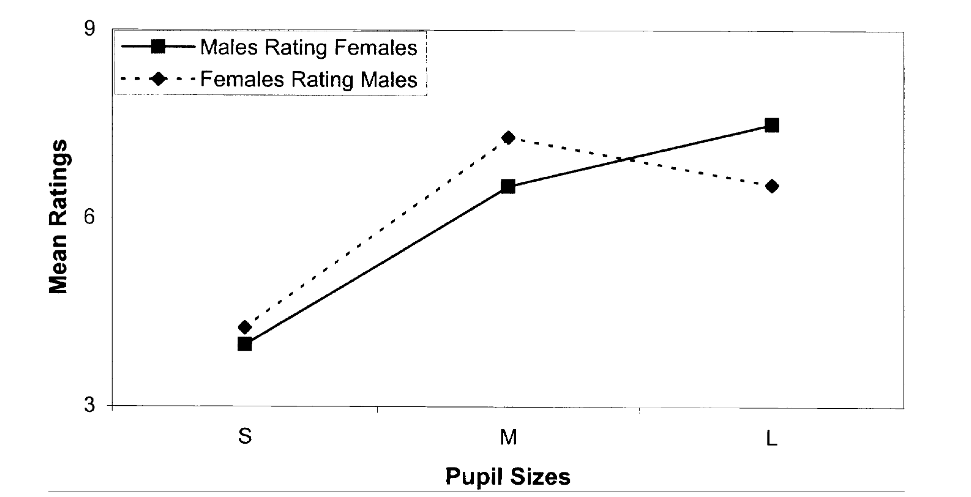

You might wonder, then: are women interested in men with large pupils? Tombs and Silverman’s 2004 paper, “Pupillometry: A sexual selection approach” tried to answer this question. The paper includes this graph:

You’ll notice that women find average pupil sizes (on men) the most attractive, while men subscribe to the Texan, bigger-is-better philosophy. The authors additionally report that, “Further investigation revealed that females attracted by large pupils also reported preferences for proverbial bad boys as dating partners.”

At this point, you might wonder why men find large pupils attractive. And, of course, evolution has good reason for that, as confirmed by a 2007 study:

We found an increase in mean pupil diameter for sexually significant stimuli during the fertile phase and this pupillary change was also specific to pictures of the participants’ actual sexual partners. Moreover, this effect was only seen for women who did not use oral contraceptives. These findings confirm that women’s attention for sexually significant stimuli is higher during their fertile phase of the menstrual cycle, and that changes in sexual interest are implicitly measurable using pupillometry.

Or, in plain English, fertile women tend to have larger pupils.

Motivation

In Elana Clift’s Honors thesis, “Picking Up and Acting Out: Politics of Masculinity in the Seduction Community,” she argues that the “pick up artist” movement is the result of the lack of available dating scripts for young men. Back in, say, Victorian England, everyone knew how this whole relationship thing worked. Today, we’re all horribly confused.

I was sorta convinced by that for a while, and I think that explains some of it, but now I’m plagued by doubt. Lots of pick-up strikes me as actively toxic. I mean, yeah, especially to women — there are a disproportionate amount of vocal misogynists associated with the “manosphere” generally, but I mean to men, too: Pick-up is an advertiser’s wet dream. Nothing sells better than insecurity, and what more poignant insecurity than masculine identity and status anxiety about attractiveness? (Whenever you hear the phrase “real” men, ask what they’re selling.)

Of course, my concerns here are hardly limited to men, although I’m more familiar with the struggles of young men everywhere. Cosmopolitan magazine is the female-equivalent of pick-up, telling young women that they need to fit into some sort of mold in order to attract a guy — that they shouldn’t answer the phone on the first ring or whatever — and I’m sure lots more nonsense which isn’t even on my radar, but probably ought to be.

Which brings me to the topic at hand: eye contact. These unsavory actors sell prolonged eye contact as some sort of panacea. An actual example I found with 10 seconds of googling: “Master These Eye Contact Techniques To Create Powerful Attraction,” complete with tips that the author promised “will blow my mind.” (Hint: they didn’t.) Another blog targeted at “Helping men reclaim their masculinity and their relationships,” (gag) includes this gem: “…strong eye contact is difficult to maintain if you do not have the confidence to back it up (thus making it an honest signal).”

Yeah, right. Because if you don’t maintain strong eye contact, it’s because you lack confidence, and definitely not because you haven’t yet mastered the serial killer’s thousand yard stare.

Frankly, this all smacks of the purest bullshit. Evolution has spent billions of years and computational cycles optimizing male-female relations. If maintaining eye contact with your crush is so effective, why don’t people just do it naturally? Could advising people to maintain strong eye contact be harmful? Maybe unnaturally strong eye contact just comes off as creepy.

I decided to find out.

The Evidence on Prolonged Eye Contact

My (somewhat begrudging) subjective feeling after reading through 5 or 6 relevant papers is that, yes, the pick-up artists are right, the majority of men ought to be making more eye contact. The case for women is less clear. As far as I can tell, too much eye contact is always better than too little, and eye contact combined with a smile is difficult to get wrong.

My neat evolution-has-optimized-eye-contact argument has at least one damning flaw: children learn the association between eye contact and liking. It’s not innate.

The association between gaze and liking appears to be learned. Children do not use eye contact to judge affiliation and friendship until about age 6 (Abramovitch & Daly, 1978; Post & Hetherington, 1974).

Now, is there such thing as too much gaze? Yes. Moderate gaze is better than constant gaze:

Gaze also influences people’s liking for each other, with moderate amounts of gaze generally preferred over constant or no gaze (Argyle, Lefebvre, & Cook, 1974; Exline, 1971).

Bu-u-u-ut constant eye contact is still better than no eye contact:

British college students rated a same-sex peer they met in an experiment as more pleasant and less nervous when the person gazed at them continuously rather than not at all (Cook & Smith. 1975).

Compare that with a mock interview study, which had students either exhibit low, natural, or high gaze. Notably, researchers defined high gaze here as near-constant eye contact. They found no difference in likability between normal and high gaze:

High-levels of gaze do not differ from normative gaze patterns in earning more favorable endorsements for hiring from an interviewer, in conferring greater credibility, in increasing attraction and in receiving favorable relational communication interpretations.

Indeed, there were even some benefits to near-constant gaze. Interviewers labeled near-constant gazers (not to be confused with goats) as more attractive, more intimate, and more dominate than those who displayed normal levels of eye contact. So, again, more evidence that too much eye-contact is way better than too little.

Those who make lots of eye contact are even judged to be more intelligent (!):

Wheeler, Baron, Michell, and Ginsburg (1979) reported a positive correlation between an interviewee’s eye contact with an interviewer and estimates made by observers of the interviewee’s intelligence.

And it’s not even confined to those you look at. If someone sees you making a lot of eye contact with someone, they’ll like you more than if you didn’t:

The positive feelings associated with gaze generalize to observers, who favor people when they gaze at moderate rather than low levels while approaching others (Gary. 1978a) or in social interactions (Abele, 1981; Shrout & Fiske, 1981).

Of course, people like it most of all when you look at them, which a 2005 study, “The look of love: gaze shifts and person perception,” verified.

Ratings of likability were elevated when social attention was directed toward rather than away from the raters.

In the same study, men rated women who paid attention to them not only as more likable, but more attractive, too:

Whereas gaze cues elevated ratings of likability among both male and female participants, only the men displayed gaze-related effects on person evaluation when the physical attractiveness of the targets was assessed.

Here’s another belief I held that turns out to be wrong. I’ve observed that people look at the speaker while listening, and look away while speaking. But this turns out to be totally okay to violate (surprise!) and you can stare all the time if you want (or, at least, high status people do it):

Equivalent amounts of gazing while speaking and listening were found with research participants who were given high status or who were discussing issues on which they had expertise (Ellyson, Dovidio, & Corson, 1981; Ellyson, Dovidio, Corson. & Vinicur. 1980).

And more eye contact makes you more powerful:

Dovidio and Ellyson (1982) reported that high gazing-while-speaking ratios were directly related to ratings of power in an interaction.

Want to make friends? Have you tried staring at people?

College women gazed more at a female confederate when they were trying to make friends (Pellegrini, Hicks, & Gordon, 1970), and college men gazed more at a woman when they wanted to interest her in a social conversation (Lefebvre, 1975).

It even holds for imaginary friends!

Mehrabian (I968a, 1968b) reported that research participants gazed more when they approached an imaginary person they liked rather than disliked.

And real ones, too:

Russo (1975) reported greater amounts of eye contact between elementary school children who were friends rather than nonfriends.

What does eye contact mean, though?

While doing keyword research for this, I noticed that a lot of men and women are confused about what prolonged eye contact means. Does it indicate sexual interest? Well, it definitely can!:

Participants in a study by Griffitt, May, and Veitch (1974) gazed more at opposite-sex peers when they had previously been exposed to sexually arousing slides.

It might even imply that you’re smokin’ hot (and trust me, gentle reader, you totally are):

Coutts and Schneider (1975) reported positive correlations between gaze directed by research participants toward opposite-sex peers and experimenter ratings of the peers’ physical attractiveness.

But not always. People will look at you more even if you’re just plain nice to them:

People gazed more after receiving positive evaluations (Coutts, Schneider, & Montgomery, 1980; Exline & Winters, 1965; Walsh et al., 1977) or warm nonverbal responses (Ho & Mitchell, 1982).

Is eye contact ever bad?

Even if you’re hitchhiking, more eye contact is better:

Drivers were more likely to stop for gazing hitchhikers (M. Snyder, Grether, & Keller. 1974), pedestrians were more likely to help a gazing experimenter pick up dropped coins (Valentine, 1980) and dropped questionnaires (Goldman & Fordyce, 1983), and bystanders were more likely to help an injured gazing jogger (Shetland & Johnson, 1978).

Or when you’re buying cereal, according to the 2014 study, “Why Is Cap’n Crunch Looking Down at My Child?”:

We showed that eye contact with cereal spokes-characters increased feelings of trust and connection to the brand, as well as choice of the brand over competitors

Now, you might wonder: are there ever times where you shouldn’t make so much eye contact? Well, when waiting for a green light:

Ellsworth et al., (1972) and Greenbaum and Rosenfeld (1978) had experimenters stand on street corners and gaze constantly or not at all at pedestrians and motorists who were waiting for a red light. When the light changed to green, pedestrians and drivers crossed the intersection significantly faster when they had received constant gaze from the experimenter.

But just dress nice and you’re okay:

For example, pedestrians did not cross the street as fast to escape a staring experimenter when the experimenter was dressed and made up to be physically attractive (Kmiecik, Mausar, & Banziger, 1979)

Or add a smile:

People were also less likely to avoid a staring experimenter when the experimenter smiled (Elman, Schulte. & Bukoff. 1977).

Sex Differences

It turns out, though, that there are sex differences. Women (on average) respond positively to lots of eye contact, while men prefer less. For instance, if you want a female friend to reveal all her secrets, eye contact is good:

Female speakers disclosed more personal information about themselves to listeners who gazed. Female speakers also liked gazing listeners more than nongazing listeners. (Ellsworth and Ross 1975)

For men, though, the opposite is true:

Male speakers, in contrast, disclosed more and felt greater liking when the listener did not gaze.

A similar phenomenon holds with asking for help when picking up coins:

For example, women gave more help in picking up dropped coins to a female experimenter who gazed at them (Valentine & Ehrlichman, 1979). Men gave more help to a male experimenter who did not gaze at them.

Women even like it when they’re told that a man looked at them an unusually high amount:

Kleinke et al. (1973) introduced college men and women in pairs and left them in a room to get acquainted. After their conversation, an experimenter told participants that one person (whose gaze was supposedly recorded through a one-way mirror) had gazed at the other person an unusually high, an average, or an unusually low amount of the time. Women were most favorable toward men whose gaze had ostensibly been high.

But not men:

Men’s reactions were exactly opposite. Men were most favorable toward women when they were told the woman’s gaze or their own gaze had been low.

I wonder if this is just male insecurity? If I was told some chick had been staring at me, I might wonder, “Is there something wrong with my hair? Has one of my legs grown two legs and walked off of its own volition?”

Does eye contact cause love?

To see is to devour.

—Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

Finally, though, what you really want to know: if I maintain eye contact with my crush, will they fall madly and deeply in love with me? Well, sorta. If you convince someone to maintain eye contact with you for ~2 minutes, they’ll (on average) be more attracted to you. The experimenters in this study told their subjects to maintain eye contact in order to “tune their extra-sensory abilities” and, afterwards, they rated their partners as significantly more attractive than controls. Hey, worth a shot, right?

Actually, it turns out, just tricking your crush into thinking they look at you a lot is enough. (“Hey, Maria, why do you keep looking at me? Is it because you’re in lo-o-o-ove with me?”)

In one of these, Kleinke, Bustos, Meeker, and Staneski (1973) did not actually induce their subjects to gaze at their partners. Instead the subjects were told that they had done so. This produced modest increases in attraction for the partner.

Further Reading

- If you want to settle down with a book on relationships, the best scientific overview I’ve read is the Handbook of Relationship Initiation. For lighter fare, The Moral Animal is pretty entertaining.

- If you liked this, you’ll love the Social Issues Research Centre’s “Guide to Flirting.”

- If you want to dive into the original sources for yourself (or look up references), start with “Gaze and eye contact: a research review,” which is where the bulk of this information came from. (Where it didn’t, I’ve indicated in the text.)

- One of the most useful bits of research to come out of the study of human relationships is the notion of the “mere exposure effect” which suggests that the more you see someone (or something), the more you’ll come to like them.