Software For Writers: Tools To Improve Your Writing

There are two types of writer — the snobs and the engineers. The engineers believe that crafting the right sentence is a rule-based affair. “Be brief. Avoid adverbs.”

The snob turns up his nose at rules. Rules, he says, are for the amateur. The English language is not about rules — great writers break them all, and those who preach about rules don’t even follow their own.

I don’t like the snobs. I mean, they have a point. In language, there are no absolutes — well, probably. But rules are useful. I suspect the real reason that snobs are so against rules is because it’s an opportunity for them to signal their sophistication. “Rules? Ick. Rules are training wheels and not for the likes of one as fine a writer as I.”

Adherents of snob theory ought to try programming. If I’m making ten mistakes an hour, it’s a good day. I’ll use any crutch available and I’ll be proud that I do. The world is a complex place. We need tools to help us tame that complexity.

Engineering in the art of writing

Spell Check

I’ve dominated more than one spelling bee in my day and used to believe that I didn’t need to spell check my work. What a poor, deluded fool I was! (I still am, but less and less and less.)

Now I spell check everything I write. I’d estimate that I have an error rate of about one or two for every 250 words. It takes 30 seconds to run a post through spell check after I write it, which is enough to eradicate the errors.

Weasel Words

Matt Might, an assistant professor at the University of Utah, wrote a set of shell scripts to help PhD students improve their writing. He focused on eliminating weasel words and passive voice. His scripts have since been ported to emacs in the form of writegood-mode.

Some examples of weasel words:

many

extremely

interestingly

surprisingly

A 2009 study analyzed the usage of the “weasel words” tag on Wikipedia and found that they fell in three broad categories:

- Handwavy use of proportion that doesn’t answer the question “How many?” (“Some people”, “Experts”, “Many”)

- Use of the passive voice.

- Adverbs, e.g. often, probably.

Such sentences can be rewritten by substituting more specific language. Wikipedia offers this example: “The Yankees are one of the greatest baseball teams in history,” can be rewritten as “The New York Yankees have won 26 World Series championships—almost three times as many as any other team.”

The principle behind this, and the “Show, don’t tell” rule so often trotted out in this sort of discussions, is to eliminate reliance on the author. If I tell you that a problem is important, you can either trust of ignore me, while if I reveal my evidence, you get to “use your own free will.”

Clichés

Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

—George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language”

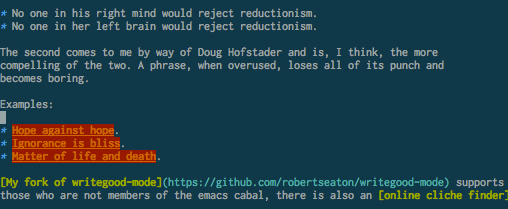

Consider two phrases:

- No one in his right mind would reject reductionism.

- No one in her left brain would reject reductionism.

The second comes to me by way of Doug Hofstadter and is, I think, the more compelling of the two. A phrase, when overused, loses all of its punch and becomes boring.

Examples:

- Hope against hope.

- Ignorance is bliss.

- Matter of life and death.

My fork of writegood-mode supports highlighting cliched phrases. For those who are not members of the emacs cabal, there is also an online cliche finder.

Grammar Checking

There are more possible errors than spelling mistakes, which is where automated grammar checkers come in. They’re not as good as human feedback, but they’re convenient and catch problems that you otherwise might not.

I ran a recent post through the open source LanguageTool and it managed to spot that I’d used “free reign,” when it should be “free rein” — a mistake subtle enough that I would never have noticed it. Hell, I thought rein and reign were spelled in the same way.

For emacs users, you can install LanguageTool and langtool-mode to check your writing from the convenience of your text editor. Non-emacs users have the option of installing and checking from the command line, or using the online version.

Readability

The average American reads at between a 7th and 8th grade level. If your prose is too complex, you’re alienating a fair chunk of potential readers.

According to Wikipedia’s article on readability, TV Guide and Readers Digest, the two publications with the largest circulation, are written at a 9th-grade level, while the most popular novels are written at a 7th-grade level. A 1947 experiment by Wallaces’ Farmer — a magazine — found that reducing an article from a 9th to 6th grade reading level increased readership by 43%.

The GNU project ships style — a command line tool that checks the reading level of a piece of writing. Running this entire blog through it returns a reading level of 8, according to the Flesh-Kincaid formula. The formula correlates 0.91 with reading comprehension.

For emacs users, there’s artbollocks-mode, which has a built-in readability test and duplicates some of the features of writegood-mode. For non emacs users, there’s GNU style and this online tool.

A Writing Checklist

In 2001, Dr. Peter Provonost — who specializes in critical care at Johns Hopkins — put together a checklist of the obvious things that doctors need to do before treating a patient: hand-washing, wear gloves, clean the patient’s skin before inserting a needle, that sort of thing. These are not super tricky, only-clever-people-know steps. Everyone is supposed to do them, everyone knows, but sometimes people forget.

After implementing the checklist, infections in the ICU dropped from 11 percent to zero — saving 8 lives and 2 million dollars. Consequently, the hospital implemented still more checklists — reducing the average ICU stay by half and saving 21 lives.

A 2009 study duplicated this success in 8 other hospitals.

Still not convinced? See my post on the effectiveness of checklists.

I have my own checklist for writing:

- Make sure all my links are to high-quality domains and treatments.

- Are links to Further Reading resources.

- Add links to other relevant posts I’ve written.

- Add images.

- Check for broken links.

- Add more relevant examples if possible, especially personal ones.

- Humanize the writing.

- Remove unoriginal metaphors or examples.

- Remove hedged phrases, weasel words.

- Switch passive phrases to active.

- Remove any foreign phrases, scientific words, or jargon that aren’t necessary.

- Read out loud and check for flow.

- Remove any criticism of other people.

- Remove cliches.

- Search for “ly” words and remove them.

- Search for exclamation marks and semi-colons and remove them.

- Strip needless words.

- Check reading level.

- Give it a good, googleable, and sensational title.

- Add a summary.

- Write google description.

- Bold the important parts.

- Have other people read it and get their reaction.

- Spell check.

- Grammar check.

- Make sure it renders properly.

Further Reading

- If you’re interested in improving your writing ability, check out my post on expertise.

- For tips on writing, there’s Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language.”