GUIDE: the best place to buy land for homesteading

There is no clean, “one size fits all” answer to the question, “Where is the best place to buy land for homesteading?” Any answer requires careful consideration of the preferences of the asker: I have a very good friend who is tragically allergic to anything green. Pollen torments him as a nightmare’s take on pixie dust. He mows the lawn and his skin cracks into sores. “You’d do well in the desert, or on a mountain,” I tell him.

My dad’s the opposite–he gets immense satisfaction from manicuring his lawn. “You ought to start a lawn service,” I tell him.

What’s your comparative advantage?

This contrast between the pollen tormented versus the lawn enthusiast is an example of comparative advantage. A lawn service run by the lawn enthusiast makes sense. A lawn service run by the lawn allergic doesn’t. One of them has a comparative advantage over the other. What’s yours?

You’ve probably heard it said that “cheap land is cheap for a reason.” This is half of a good point. Fully considered the statement ought to be, “Cheap land is cheap for a reason. When that reason doesn’t apply to you, buy that land.”

Example: The Amish often go for acreage in areas that cannot easily be connected to the electric grid. To them, this is not a downside (they have no intention of connecting to the grid) but this also means there is little competition for the land. It can be had for cheap.

What are your strengths?

In my home state of Illinois, land is expensive. It’s flat and the soil is great, which makes it perfect for farming with ultra-efficient machines that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. The result is that the land is mostly owned (or rented) by giant corporate farms: they have the necessary capital to afford the technology to make the most productive use of it.

Individual homesteaders (like you) are better off with land at the other end of the spectrum. Land with quirks. Land that resists machinery. Land with rocks and hills, like that in Appalachia or the Ozarks. (I’ll cover these especially promising regions in more detail later.)

Buy land that plays to your strengths. Ask yourself,

What are you planning to produce?

See, the problem faced by a would-be homesteader looking for land is a lot like that of an industrialist trying to determine where to place his next factory or a farmer deciding what acreage to buy. Both choices crucially depend on what they intend to produce: some land is ideal for growing corn, some for strawberries. Some regions have cheap electricity, good for mining bitcoin, while others have cheap lumber, ideal for a furniture maker.

What will you {grow, craft, build, trade, create, sell}, and what sort of property would support that?

This is a hard question to answer straight on; it’s better to come at it sideways.

What could you barter with your neighbors?

Friend, do you know of Johnny Appleseed? He’s one of my heroes: caring nothing for material possessions, he wandered the United States, freely building apple orchards along the way.

The apples weren’t for eating, though.

Really, what Johnny Appleseed was doing and the reason he was welcome in every cabin in Ohio and Indiana was he was bringing the gift of alcohol to the frontier. He was our American Dionysus.

–from The Botany of Desire as quoted on Wikipedia

They were cider apples, for getting drunk. Pre-prohibition, hard cider was America’s most popular drink. On the frontier, it was money:

Hard cider was a key component of the colonial economy since currency was often hard to come by in the colonies. There was plenty of cider to go around, though, so in the absence of money, cider became as good as cash. Colonists would pay their bills with barrels of cider and worked out barter arrangements. Cider and applejack (hard cider that had been further fortified through freeze distillation) were supposedly even used to pay the construction crews that built some of the country’s first roads.

—“The drink that built a nation”

You catch that? Hard cider, as good as cash.

Things haven’t changed much since. Alcohol is the closest thing to money a homestead can produce. It is the versatile, high-value barter item, (along with cannabis and tobacco.)

What sort of homesteading land would support brewing booze?

- If you want to produce higher-value hard liquor, Missouri is the only state with legal home distilling. (Not that I, as an agorist, think that ought to stop you.)

- Land with mature apple trees is great, if you can swing it, as hard cider is about the easiest thing to brew. Press apples with a cider press, leave the juice out for a few weeks to ferment, and presto.

- Applejack, a kind of ice-jacked cider, is the simplest hard liquor to DIY. I’ve covered how to in more detail in my Applejack brewing guide but, as far as land for it, you’ll want to be in a region with at least a few days significantly below freezing a year.

- Regarding homebrewing generally, properties with basements or cellars can be useful for temperature control. It’s also advantageous to locate close to a recycling plant for cheap glassware to bottle your product.

A more general strategy for brainstorming barter items

Scale up anything you plan on producing for yourself. Then, you can barter or sell the surplus, e.g.

- Any garden excess.

- Seeds and seedlings.

- Value-added items produced out of garden surplus, like salsas, jams, jellies, sauerkraut, canned goods.

- Extra eggs, if you raise chickens.

The natural extension of this is,

What do you plan to grow, and what region is suitable for that?

Example: Tomatoes do poorly in the pacific northwest. Although the region rarely freezes, the climate is too temperate. The region’s summer highs are not enough for tomatoes.

Example: If you want to grow corn, you’re going to need to be east of the 100th meridian. West of it and you’re probably looking at wheat.

Example: Quinoa is a particularly interesting staple crop and superfood. (It’s been selected to feed astronauts on long-duration human occupied space flights.) US cultivation is however experimental and mostly limited to cool mountainous regions like Idaho. Amaranth is a similar crop that’s suited for warmer areas.

You’ll want to carefully consider how well the soil and climate in any region will support your preferred crops.

Remember: most fruit trees (apples, pears, peaches) require a certain amount of chill hours every season. If you want to grow apples and you settle in Zone 8 or warmer, you’re gonna have a bad time.

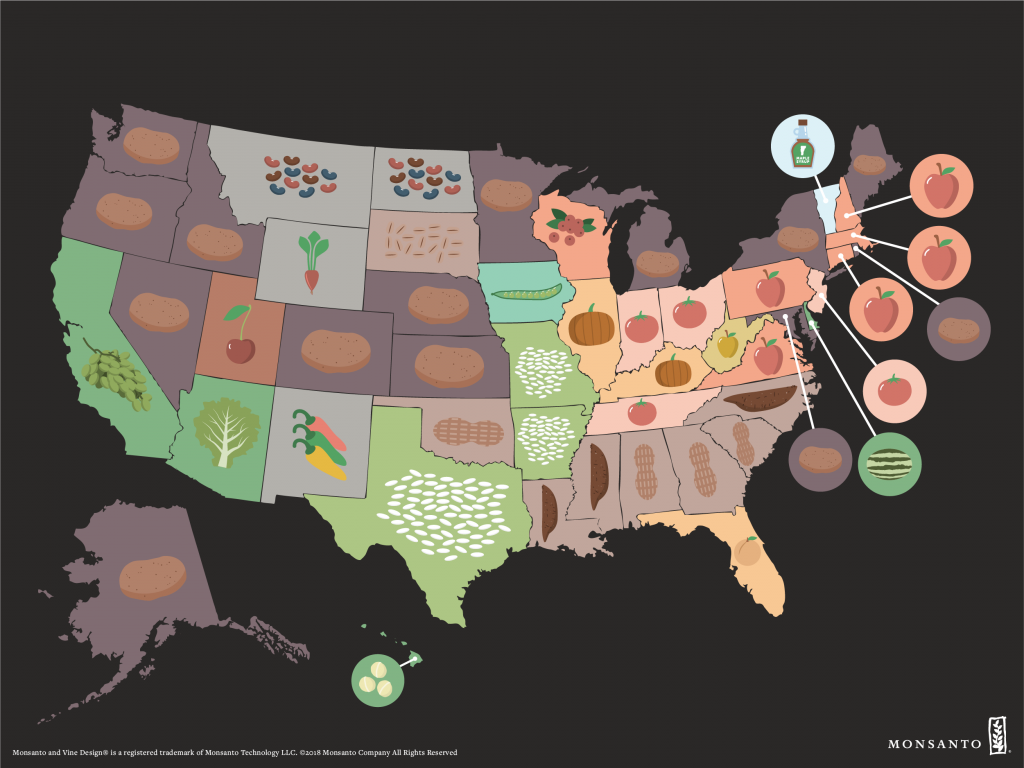

Once you’ve an idea of what you’d like to grow, you can find promising areas by figuring out which regions are already producing most of it. Monsanto has such a page, “The United Crops of America,” which includes this map:

The USDA has a similarly useful tool where you can explore agricultural exports by state and commodity.

What are your hobbies and interests?

Likewise, almost any hobby or interest can be decomposed into potential hustles for the homesteader:

Example: I’m tragically addicted to hot peppers. I started growing them just for me and, along the way, realized they can be sold as whole peppers, pickled slices, pickled whole, hot sauce, dried whole, ground into powder, as seeds, and as seedlings.

If you build your own grow lights to start your seedlings, you could sell those, too. Lower tech option: build cold frames for seed starting out of salvaged windows.

Example: Beekeeping. You can raise and sell bees, queens, honey, beeswax, bee-removal and pollination services. If you learn to build your own hives, you can craft and sell those, too.

Example: Woodworking in general strikes me as a very promising potential niche for a homesteader. Buy a plot of wooded land, get a cheap sawmill from Harbor Freight, mill and sell your own lumber, or use it to build a house, or turn it into custom furniture, beehives, or chicken coops. Here’s the story of a man who did just that.

The general idea here is to take something you know about or are interested in knowing about and start looking at everything surrounding it. What potential is there? What could you make?

Same with your labor: what skills do you have that could be of use to your neighbors? Can you fix computers, or cars? Could you help them sell things on eBay, Craigslist, or create a website? If you plan on getting a tractor, you could put up an ad to till up gardens: I’d hire you.

Once you have a list like this of your own, start thinking about what sort of land would compliment it. A woodworker will want to be close to cheap lumber, for example. Or, if you plan on producing a lot of cider, you’ll want to be either somewhere where you can grow your own apples or have neighboring farms that do. A beekeeper will be better served by a warm climate with winters too mild for apples.

Here are a couple of threads with more ideas:

What’s the farthest you are willing to go? The United States, or the world?

One of the early decisions you’re going to want to make is whether to limit your search to the United States (or your home country), or if you want to consider the entire world.

Personally I limited my search to “only” the United States. I worried about navigating the legal and cultural systems of foreign countries, and didn’t feel confident that said nations would support my property rights if they were to ever come into conflict with a native. I’m thinking of the appropriation of white-owned farmland in Zimbabwe here, as well as Joel Salatin’s father, who was forced to abandon his homestead in Venezeula.

If you are interested in homesteading outside of the US, here are some external resources:

- Anyone consider homesteading outside the USA? (reddit discussion)

- This permies thread recommends Costa Rica and Bulgaria

How remote is “just right?”

Do you want to go off-grid and generate your own power?

Properties with sloping streams are especially promising for off-grid power generation, as they can support micro-hydro where as long as the stream is running, there’s consistent, steady power available. This means you don’t have to invest tens of thousands of dollars into an expensive battery bank to handle the peakiness of technologies like solar or wind.

Here are a couple examples of micro-hydro projects:

Could you live on an island?

If you’re open to living on an island, don’t overlook Hawaii. Land is surprisingly affordable–Landwatch’s cheapest 3 acre parcel is 14k–and the climate can’t be beat: in many areas a tent is sufficient shelter.

The tropical climate also opens up crop possibilities that cannot be had on the mainland, like growing coffee or durian fruit, and year round, too. Indeed, as far as I can tell, there is nowhere in the United States where it is easier to grow most of your diet than Hawaii.

There is also abundant rain and sun for collection, and in some regions going off-grid is necessary: utilities will not be (re)built in regions prone to lava flows. Fortunately, if that doesn’t bother you, the land can be had at a discount.

Of course, it’s not all good: There is no frost to act as a ‘reset’ by killing insects and disease. Everything is expensive. Some people go stir crazy on an island. Land rights can be complicated.

- Homesteading in Hawaii (reddit discussion)

- More advice on Hawaii from reddit

- Homesteading Today thread on Hawaii

- If you like the romantic idea of island life, be sure to check out An Island to Oneself.

…a Spanish speaking island?

If Hawaii seems OK, Puerto Rico is an option to consider, too. Land is even cheaper there, and it’s closer to the mainland. Taxes are lower, too.

Downsides: corruption, crime, everything is in Spanish.

What’s your climate?

There was something that really bothered me about living in San Francsico–well, apart from the politics and the rent–no hot summer nights. Out West, there’s not the humidity like in my home state of Illinois. It cools off at night, always

It just felt wrong. Something missing. I like those humid days when your clothes stick to you, when the air is heavy and oppressive, later to be punctuated by thunderstorms–that’s something else I missed, too.

I didn’t miss the snow.

Where do the laws support you?

As far as actual laws and policy are concerned, a great resource is the Freedom in the 50 States website. The site allows you to create a custom ranking based on your personal preferences regarding rules and regulation (raw milk, etc).

Here’s what mine looks like:

Where does the culture support you?

The best description of the different cultures of the United States I’ve read is from Colin Woodward’s American Nations. Here’s what his breakdown looks like:

I’ve copied Woodward’s summaries of the regions here, although you really ought to read the book.

- Yankeedom values education, intellectual achievement, communal empowerment, and citizen participation in government as a shield against tyranny. Yankees are comfortable with government regulation. Woodard notes that Yankees have a “Utopian streak.”

- New Netherland is “materialistic, with a profound tolerance for ethnic and religious diversity and an unflinching commitment to the freedom of inquiry and conscience,” according to Woodard. It is a natural ally with Yankeedom and encompasses New York City and northern New Jersey.

- The Midlands are a welcoming middle-class society that spawned the culture of the “American Heartland.” Political opinion is moderate, and government regulation is frowned upon. Woodard calls the ethnically diverse Midlands “America’s great swing region.”

- Tidewater was built by the young English gentry in the area around the Chesapeake Bay and North Carolina. Starting as a feudal society that embraced slavery, the region places a high value on respect for authority and tradition.

- Greater Appalachia is stereotyped as the land of hillbillies and rednecks. Woodard says Appalachia values personal sovereignty and individual liberty and is “intensely suspicious of lowland aristocrats and Yankee social engineers alike.”

- The Deep South was established by English slave lords from Barbados and was styled as a West Indies-style slave society, Woodard notes. It has a very rigid social structure and fights against government regulation that threatens individual liberty.

- El Norte is “a place apart” from the rest of America, according to Woodard. Hispanic culture dominates in the area, and the region values independence, self-sufficiency, and hard work above all else.

- Colonized by New Englanders and Appalachian Midwesterners, the Left Coast is a hybrid of “Yankee utopianism and Appalachian self-expression and exploration,” Woodard says.

- Far West: The conservative west. Developed through large investment in industry, yet where inhabitants continue to “resent” the Eastern interests that initially controlled that investment.

- New France: A pocket of liberalism nestled in the Deep South, its people are consensus driven, tolerant, and comfortable with government involvement in the economy. Woodard says New France is among the most liberal places in North America.

You can get a better feel for the differences between the cultures by checking out JayMan’s “Maps of the American nations “ and “More maps of the American nations.”

As best I can tell, while you can homestead anywhere, the cultures most agreeable for homesteaders are the Left Coast, Greater Appalachia, and the rural parts of Yankeedom, e.g. Vermont and Maine.

Where are your people?

There are two big ways of thinking about this question, I think. The first way is to focus on your existing relationships, “Where are my friends and family at? OK, that’s where I’ll go.”

The second way is to focus on, “Where might I potentially fit in better than I do here, now? Forget about my current friends; where are my potential friends?”

You might, for instance, want to live in a place where the people are genetically similar to you,

Or where the people have personalities like yours,

Or maybe just in one that shares your politics,

Or where the people talk like you,

Or, hell, maybe just where they feel the same about cats vs dogs,

Where can you afford?

In my experience, a comfortable majority of land listings are created by insane people. These folk live in a fantastic world of pure imagination and believe, reality be damned, that their property is worth a substantial multiple over what similar parcels are actually selling for.

Land websites are absolutely jammed with such listings. Properties priced properly eventually sell; everything else stays on the market forever.

Thus, a rule: Never base your opinion on what land in an area is worth on listed asking prices. Only pay attention to sold listings. The numbers that matter are what parcels have actually sold for.

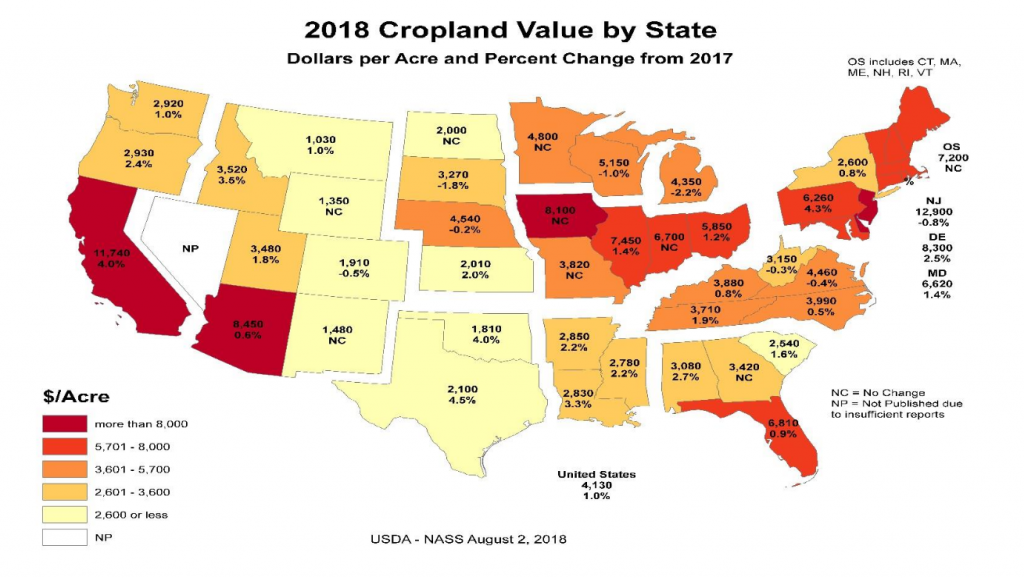

Luckily, the USDA compiles just such a census every year. Here are the state averages for cropland in 2018:

Looking at this map, you can get a good base rate for what an acre of good cropland in a given state is worth, on average, along with an understanding of the relative price of land in different states.

Remember earlier how I mentioned land in Illinois being more expensive than land in Appalachia or the Ozarks? You can read that right off this map: Illinois is ~7500/acre. Appalachia and the Ozarks are closer to half that, and these numbers are for cropland. Expect more marginal acres, like timberland or grazing prarie, to be worth much less.

How To Use Zillow to Price Specific Regions

While a statewide average is good enough for many states, in some it is more misleading than not. Check out the numbers for Oregon and Washington, for example. If you’re looking for land on the wet side of the Cascades, you’re not going to find acreage for ~2,900/acre unless you’re the world’s luckiest son-of-a-bitch. The numbers here are being skewed by the much cheaper land on the dry side.

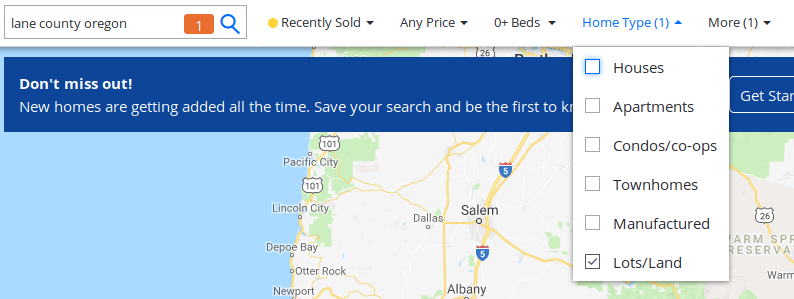

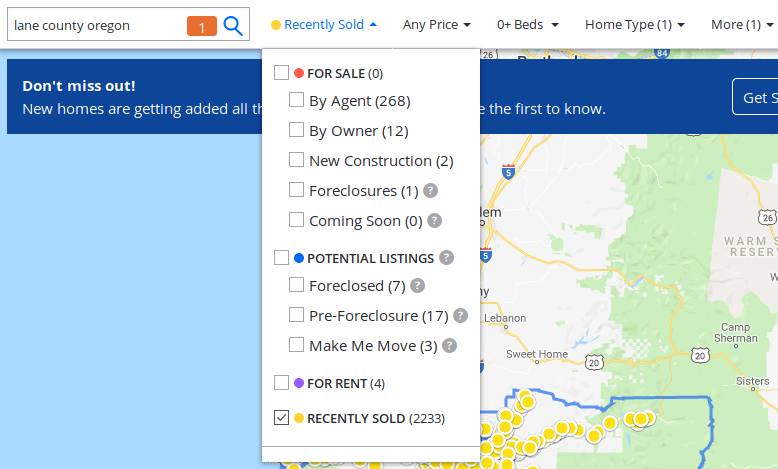

Zillow to the rescue! For a specific region, you can get a sense of land values by going onto Zillow, searching for the county you want, restricting your search to land only, and then setting the results to display sold listings only.

This’ll show you all of the recently sold land listings. Scrolling through them, you’ll get a sense of what acreage is actually going for. Looking up the wet side of Oregon near Eugene this way, you’d be doing well if you find anything for less than 10k/acre.

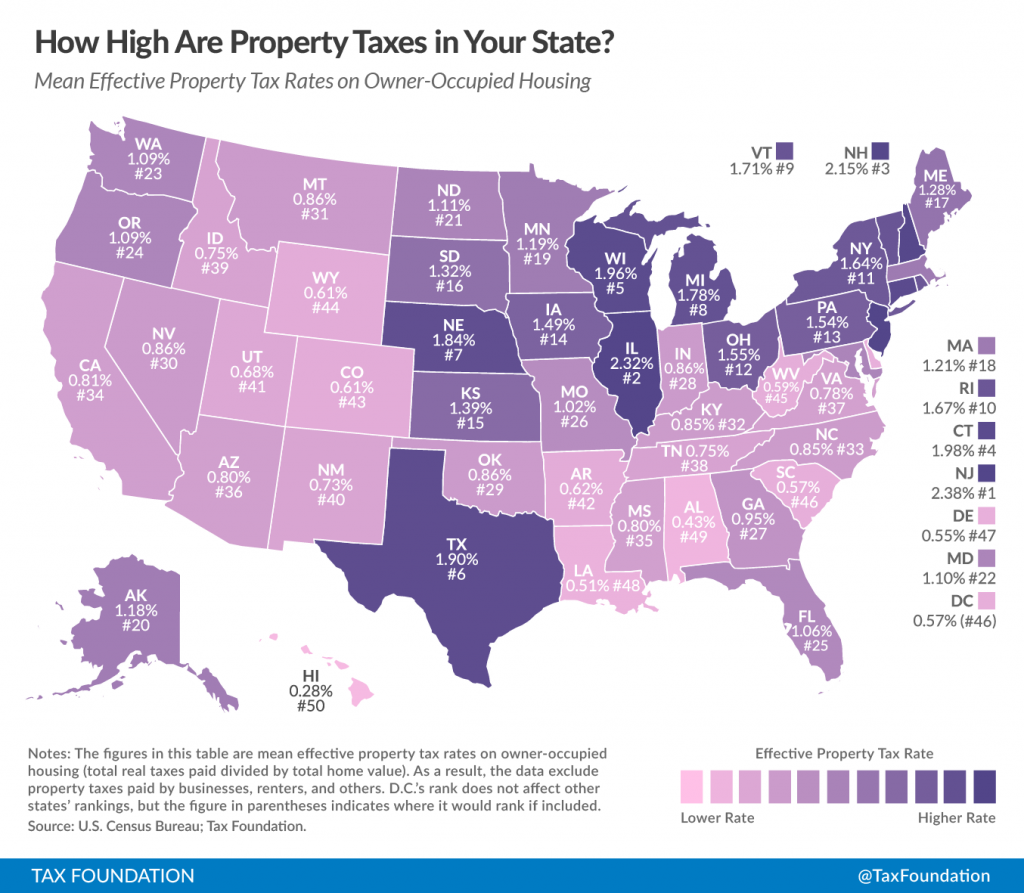

Don’t Forget Property Taxes

Going back to our Illinois versus Appalachia and the Ozarks example, the gap is actually even larger than it appears from the initial purchase price, as that doesn’t take into account yearly property tax payments–which are about 3x higher in Illinois.

In fact, a chart like the above is just the beginning of figuring out differences in tax burden between states. Texas, for instance, is listed here as the state with the sixth highest property tax but this is misleading as a homesteader’s property would likely qualify for the homestead exemption.

Similarly, Montana’s property taxes may be low but, if you decide on that alone, you’ll be in for a rude awakening after moving and discovering that the state also charges special yearly fees per head of livestock. These sort of taxes are rarely included even in rankings that claim they measure overall tax burden, like WalletHub’s, which doesn’t account even for relatively major, standard taxes like those on gasoline. It has a long way to go before it’ll be updated to include hidden livestock fees.

Ultimately you’re going to have to personally, carefully research the tax situation of any region to get an accurate picture of the actual costs of living there. Watch out for gotchas like Michigan where, thanks to some ill considered laws, car insurance is $346 higher than the national average.

As Far As Your Dollar Can Go: Specific Regions

The Desert

The absolute cheapest acreage you’ll find in the United States is desert land in Western states like Nevada. Parcels routinely sell on eBay for $250/acre. Likely it can be had for less if you do some digging and contact locals directly, instead of relying on the internet. I’m betting if you’re clever you can get down to $100/acre.

–actually, looking now, it appears land in Nevada can sometimes be had for $100/acre on eBay. Maybe you could get it down to $50, then.

If you want cheap space, don’t mind trucking in water and don’t plan on growing crops (or want a challenge), consider this region. Solar power is extremely viable, getting cheaper every day, and, if you don’t (yet) understand the appeal of arid spaces, start by reading Desert Solitaire.

- The Permies website has a sub-forum dedicated to “greening the desert” that’s full of information on desert living. There’s a thread on revitalizing 10 acres in the dry part of Texas that I imagine is very applicable to 10 acres of desert.

- Advice on homesteading in the desert.

- More advice.

- Even more advice.

Inland Maine

If the desert is too dry and you want land that gets plenty of rainfall, the cheapest you’ll find is in Maine’s interior, such as Aroostook County. Land can be had for $500/acre on websites like LandWatch and likely for a bit less by getting into direct contact with locals. The region also has a lot of homesteaders and a very supportive culture.

The downside is that it is cold and remote. Winter is long, with a lot of snow. Consequently, you have a growing season that’s on the shorter side, around 4 months.

- Permies thread on homesteading in Maine.

- I gave up my 6-figure desk job to live in a cabin with no electricity and no running water. I live on about $2,000 a year doing odd jobs here and there, the rest of my time is devoted to my hobbies. I love my life. AMA

The Ozarks of North Arkansas

If you want land with water somewhere warmer than Maine, the cheapest you’ll find is probably in the Ozarks on the Arkansas side, where land can be found for a bit less than $1000/acre.

The difficulty is finding soil that’s worth a damn. It’s out there but it’s not the norm: most of the Ozarks is rocks, clay, and little or no soil. The decent soil is mostly in the former riverlands scattered throughout the area. (In the past I’ve used AcreValue to help determine the soil quality of different parcels.)

The region is also, of course, hilly, and best suited to intensive gardening and not machine cultivation.

Recommended Further Reading

- For a more “prepper”-centric take on this topic that focuses more on catastrophic disasters, check out the book Strategic Re-Location.

- For understanding the different regions of the United States, start by reading American Nations. If you want more after that, read Who’s Your City? and Our Patchwork Nation.