The Science of Habit

The truth is that everyone is bored, and devotes himself to cultivating habits.

—Albert Camus, The Plague

To my perpetual dismay, I’m not a rational agent with limitless willpower. I’m not every moment brimming with novel insight and original computation. No. I’m a habit machine, a behavior-executor, on autopilot — a creature of habit. (Or “habbit,” for illiterate googlers.) I do the things that I do because that’s how I’ve done them in the past.

How horrible — but no, habits are adaptive. They are a good thing. Don’t believe the popular wisdom. We’re habit machines. Embrace it. Without habit, you would have to think through all the small things — will I have coffee with breakfast? Should I brush my teeth before or after showering? How do I tie my shoes? Ad infinitum.

Something like this does happen with Parkinson’s patients. The disease damages regions key to habit formation — the basal ganglia and company. This interference results in sufferers performing poorly on a number of laboratory tasks. Less habity-ness than a healthy brain: not positive, not a good thing, not beneficial.

Too much habity-ness is a problem, too. The drugs used to treat Parkinson’s can lead sufferers to develop gambling or sex addictions. Some of the symptoms of OCD look an awful lot like problems with habit — repetitive thoughts, urges to engage in certain rituals, grooming behaviors (hand washing), and more. (Wikipedia lists hair-pulling as a symptom of OCD. I dated a chick with OCD once and she would pull out her hair, so I can very scientifically confirm the truth of this.) The compulsions of OCD are the result of taking the “force” in “force of habit” and amplifying it.

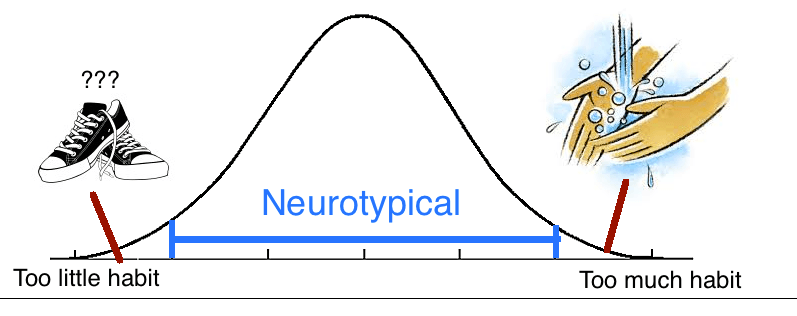

There is a habit spectrum with those who have trouble establishing habits — Parkinson’s disease patients — on one end and those who form habits too easily — OCD — on the other end. In fact, Lally et al. found that there is significant individual variation in habity-ness. For a habit to reach its peak, it took subjects anywhere from 18 to 254 days, with a median of 66 days.

We can visualize this as a probability distribution, in which it takes most people around 66 days to establish a new habit, but with significant variation. The tails of the distribution are characterized by pathology, e.g. OCD and Parkinson’s.

Why Should I Care?

Human behavior is like a natural disaster, an avalanche or a forest fire. You can nudge the Titanic, schedule a controlled burn, and build avalanche barriers, but that’s about the extent of it. These are the equivalent of establishing the right habits during periods of high motivation and control. With consistent nudging, you can set yourself onto a new path.

Consider the man gracing the one-hundred dollar bill, Benjamin Franklin. He was interested in cultivating virtue — contrast with our modern obsession with personality — and developed a system for doing so, writing in his autobiography, “the contrary habits must be broken, and good ones acquired and established.”

He created a weekly chart, marking it “by a little black spot” whenever he failed to live up to one of his 13 virtues. On any given week, he would focus on just one of the virtues. Of his system, he writes, “I was surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined; but I had the satisfaction of seeing them diminish.”

This is all to say that the essence of a man is, in some sense, what he does out of habit. A mathematician is defined by his habit of doing math, a programmer by his habit of programming, and a writer of his habit for writing. To be a kind person, be kind out of habit. To the extent that enduring personality can be shaped and modified, habit is the way.

Consider competence. Excellence in anything is the result of practice. How does one chew through a mountain of practice? Out of habit. If you develop a habit of setting aside a few hours each day to push through your boundaries, this habit will propel you to excellence. This is what the development of expertise looks like. It looks like a habit of waking up at 5 in the morning to do laps in the pool.

What is a Habit?

My friends were wise men of the first rank, and we found the problem soon enough: coffee wanted its victim.

—Honore de Balzac, The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee

A habit is an automatic behavior, repeated often. There is often a cue that prompts it. I have a coffee habit, triggered by sleepiness, waiters asking if I would like coffee, the smell of coffee, reading about coffee and, as I’m just now discovering, also writing about coffee. The caffeine barricades my adenosine receptors and releases a flood of dopamine, reinforcing the behavior. A habit is born.

We can take nervous habits as an example as well, such as stroking the neck. These sort of self-soothing gestures are cued by internal feelings of distress, which launches the behavior (neck rubbing). The reinforcement here is the resulting decrease in distress.

Cigarette smoking works in much the same way. Many people smoke when they wish to relax, so it can be cued by internal feelings of tension. This triggers getting out the cigarette and smoking it, which provides a hit of nicotine. The nicotine acts on the brains reward system, which reinforces the behavior. (Nicotine’s role in encouraging habit formation is why it can be so difficult to quit.)

However, this process is not carved in stone. There are some habits which don’t have clear cues or rewards. As part of writing this, I set my phone to buzz at random intervals during the day, at which point I’ve been reciting the poem “Invictus.” There’s no clear reward, but habit formation has been chugging along nonetheless.

As my Invictus example implies, there are mental habits, too, and they function in the same way. When you mention Illinois State University, my mother — without fail — will say, “Go salukis!” (Her alma mater’s mascot.) When I hear someone say “Turn it up”, a Filip Nikolic remix of “Bring the Noise” hijacks the helm of my consciousness and steers it to the melody of that beat.

Somewhat troubling is the realization that most of our thought is not internally generated, but scripts that run as a result of external cues. Patients presenting with transient global amnesia are a dramatic example of this. Unable to commit anything to long term memory, they continue to execute the same loop of behavior, repeating the same conversations over and over. Radiolab has great coverage of one case in their “Loops” episode.

Habit Formation

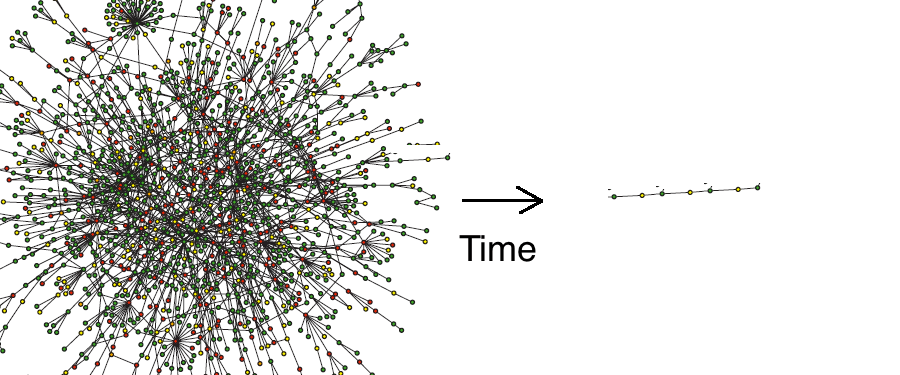

When a habit is first being formed, it consists of deliberate, effortful, goal-based activity. This is supported by brain scans, which show activity in the prefrontal cortex — the front brain, sometimes called the seat of reason. For those familiar with dual process theory, this is system 2 behavior.

In the beginning stages, behavior is flexible. Each act of the behavior in question can be thought of as an original (and thus effortful) computation.

As the behavior is repeated, it becomes less effortful, and brain activity begins to shift. Activity in the prefrontal cortex dies down and activity moves into lower, more central brain regions — mainly the basal ganglia. The behavior itself becomes less flexible. The process is much like the life-cycle of a clay bowl: first, wet clay is malleable, but — once fired in a kiln — it hardens and is ready for use.

For those comfortable with computational metaphors, we can imagine habit formation first as a sort of graph search — trying to find the right sequence of actions that lead to some reward, like alpha-beta search in a chess engine. With time, the brain learns when one path is often retrieved. It “saves” that path and executes that in the future, avoiding a whole lot of computation, but at the cost of flexibility. The graph search corresponds to activity in the prefrontal cortex, while the saved path is executed by the basal ganglia.

The Progress of Habit

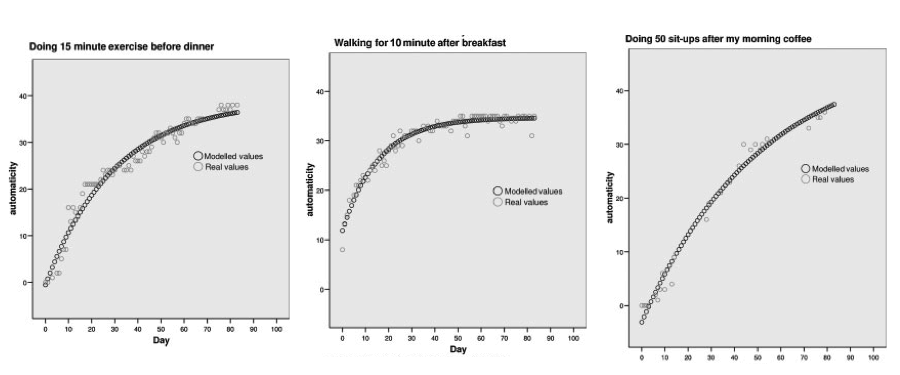

The interplay between automaticity and repeated behavior gives us a visual of habit formation over time.

The picture above is what an activity looks like over time as it solidifies into a habit. It starts hard and effortful. With each execution of the behavior, it becomes more automatic and natural, until it reaches an asymptote. At this point, it levels off and has become a bona fide habit.

Cultivating Good Habits

Thus far, the discussion has been theoretical. We are interested in habits, though, in what they can do for us. We would like to cultivate the right sort of habits in order to become the person that we would like to be.

The science suggests a few guidelines.

- First, everything becomes easier with practice. This alone is motivating.

- To cultivate a habit, do that thing as often as possible. The time to enact new habits is in when a high motivation state.

- Create some cue to prompt the habit. A cell phone alarm is good for this. You can use the TagTime Android application to set up random pinging throughout the day.

- After the good habit has been executed, reward it in some way. M&M’s are a popular reinforcer, but even positive self-talk can be effective. Some people even use nicotine.

- There are a number of productivity tools that make habit formation easier, like HabitRPG, chains.cc, Pomodoro timers, and BeeMinder.

Breaking a Bad Habit

The way that people often go about stopping a bad habit is by attempting to just “use their free will” to quit doing it. This does not often work, as evidenced by all of the people who have such difficulty with their fitness goals or quitting smoking.

If you have a specific habit you would like to stop, I would first suggest looking for resources specific to those habits. There are already good resources for those trying to quit smoking, but I’ll admit that I looked around and most guides were not that compelling.

There are a few ways to tame a bad habit. The first is to understand the context of the habit. What’s the cue? What’s the reward? Once you’re able to notice this, it becomes possible to gain some measure of control over it. You can try to figure out a path to removing the cue or the reward, or even replacing it with a disincentive, like when nail-biters coat their nails in something bitter.

Alternatively, and I think this is the best option, is to establish a new habit in place of another, to fight fire with fire. Eating junk food is a habit that many would like to stop, but this is the wrong way of looking at things. One ought to try to eat more healthy food. The junk food will fall by the wayside. For those who wish to stop eating meat, frame it not as “stop eating meat” but instead as eating more plant-based meals.

This is the difference between approach and avoidance goals. Approach goals are framed as something you want to do, while avoidance goals are framed as something you want to avoid. Approach goals (such as eat more vegetables) are more energized over time and more likely to be achieved. Reason #45820 the human brain is hack: just reframing your goals as approach instead of avoidance can improve your odds of completing those goals.

Putting it All Together

To recap:

- A habit is a behavior that becomes automatic and effortless with repetition.

- Habits are important because so much of our behavior happens outside of conscious control. Developing the right habits allows us to modify who we are.

- A habit consists of a cue which triggers a behavior which is then reinforced.

- Habits start effortful and goal-directed, but become effortless and automatic with repetition.

- Habitual behavior becomes less flexible over time and can be conceptualized as the migration from graph search to a fixed sequence of behavior. This is computationally cheaper.

- There are several technologies available that can aid in habit formation.

- To conquer a bad habit, notice what cues the habit and then try replacing it with a new, better habit or by removing those cues.

Further Reading

- I have written a similar post on human expertise.

- For information on different brain structures involved in habit formation, see the paper “Habits, Rituals, and the Evaluative Brain.”

- For a more in-depth overview of the computational model of habit creation presented here, see the paper “Uncertainty-based competition between prefrontal and dorsolateral striatal systems for behavioral control.”

- There is a book called The Power of Habit which you could check out, or you could read this summary and get most of the value in a fraction of the time.

- The book Don’t Shoot the Dog has lots of good information on reinforcement strategies and behavior change. There is a summary here.

- For techniques on overcoming procrastination (that black dog!), there is valuable information here and I also recommend Piers Steel’s book The Procrastination Equation.