The Science of Problem Solving

Mathematics is like the One Ring in the Lord of the Rings. Once you’ve loaded a problem into your head, you find yourself mesmerized, unable to turn away. It’s an obsession, a drug. You dig deeper and deeper into the problem, the whole time unaware that the problem is digging back into you. Gauss was wrong. Mathematics isn’t a queen. She’s a python, wrapping and squeezing your mind until you find yourself thinking about the integer cuboid problem while dreaming, on waking, while brushing your teeth, even during sex.

Mathematics is like the One Ring in the Lord of the Rings. Once you’ve loaded a problem into your head, you find yourself mesmerized, unable to turn away. It’s an obsession, a drug. You dig deeper and deeper into the problem, the whole time unaware that the problem is digging back into you. Gauss was wrong. Mathematics isn’t a queen. She’s a python, wrapping and squeezing your mind until you find yourself thinking about the integer cuboid problem while dreaming, on waking, while brushing your teeth, even during sex.

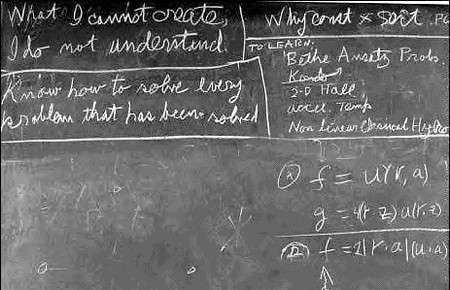

Lest you think I exaggerate, Feynman’s second wife wrote in the divorce complaint, “He begins working calculus problems in his head as soon as he awakens. He did calculus while driving in his car, while sitting in the living room, and while lying in bed at night.” Indeed, the above is a picture of Feynman’s blackboard at the time of his death. It says on it, “Know how to solve every problem that has been solved.” I like this sentiment, this idea of man as problem solver. If I were running things, I think I would have sent Moses down the mountain with that as one of the ten commandments instead of two versions of “thou shalt not covet.”

That’s what this post is about: How do humans solve problem and what, if anything, can we do to become more effective problem solvers? I don’t think this needs any motivating. I spend too much time confused and frustrated, struggling against some piece of mathematics or attempting to understand my fellow man to not be interested in leveling up my general problem-solving ability. I find it difficult to imagine anyone feeling otherwise. After all, life is in some sense a series of problems, of obstacles to be overcome. If we can upgrade from a hammer to dynamite to blast through those, well, what are we waiting for? Let’s go nuclear.

A Computational Model of Problem Solving

Problem solving can be understood as a search problem. You start in some state, there’s a set of neighbor states you can move to, and a final state that you would like to end up in. Say you’re Ted Bundy. It’s midnight and you’re prowling around. You’re struck by a sudden urge to kill a woman. You have a set of moves you could take. You could pretend to be injured, lead some poor college girl to your car, and then bludgeon her to death. Or you could break into a sorority house and attack her there, along with six of her closest friends. These are possible paths to the final state, which in this macabre example is murder.

Similarly, for those who rolled lawful good instead of chaotic evil, we can imagine being the detective hunting Ted Bundy. You start in some initial state — the Lieutenant puts you on the case (at least, that’s how it works on television.) Your first move might be to review the case files. Then you might speak to the head detective about the most promising leads. You might ask other cops about similar cases. In this way, you’d keep choosing moves until reaching your goal.

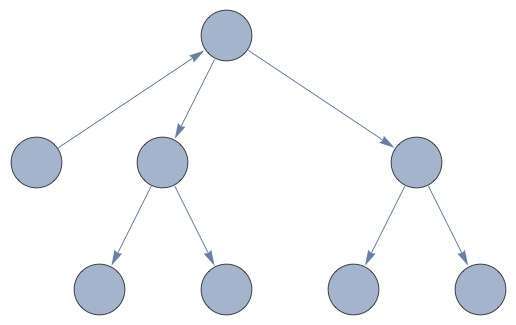

Both of these are a graph. (Not to be confused with the graph of a function, which you learned about in algebra. This sort of graph — pictured below — is a set of objects with links between them.) The nodes of the graph are states of the world, while the links between the nodes are possible actions.

Problem solving, then, can be thought of as, “Starting at the initial state, how do I reach the goal state?”

On this simple graph, the answer is trivial:

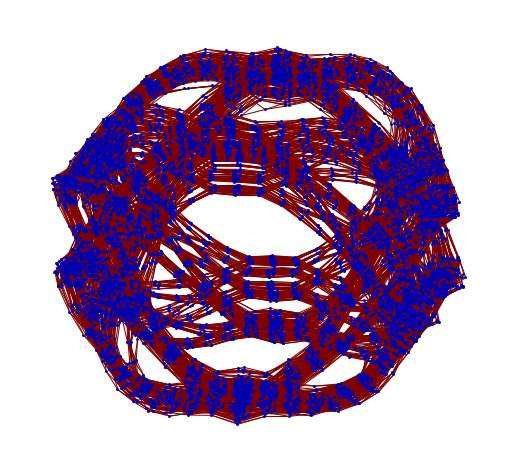

On the sort of graph you’d encounter in the real world, though, it wouldn’t be so easy. The number of possible moves in a chess match — itself a simplification when compared to, you know, actual war — is \( 10^{120} \), while the number of atoms in the observable universe is a mere \( 10^{81} \). It’s a near certainty, then, that the human mind doesn’t consider an entire graph when solving a problem, but somehow approximates a graph search. Still, it’s sorta fun to imagine what a real world problem might look like.

Insight

A change in perspective is worth 80 IQ points.

—Alan Kay

Insight. In the shower, thinking about nothing much, it springs on us, unbidden and sudden. No wonder the Greeks thought creativity came from an outside source, one of the Muses. It’s like the heavens open up and a lightning bolt implants the notion into our heads. Like we took an extension cord, plugged it into the back of our necks, and hooked ourselves into the Way, the Tao, charging ourselves off the zeitgeist and, boom, you have mail.

It’s an intellectual earthquake. Our assumptions shift beneath us and we find ourselves reoriented. The problem is turned upside down — a break in the trees and a new path is revealed.

That’s what insight feels like. How does it work within the mind? There are a number of different theories and no clear consensus among the literature. However, with that said, I have a favorite. Insight is best thought of as a change in problem representation.

Consider how often insight is accompanied by the realization, “Ohmygod, I’ve been thinking about everything wrong.” This new way of thinking about the problem is a new representation of the problem, which suggests different possible approaches.

Consider one of the problems that psychologists use to study insight:

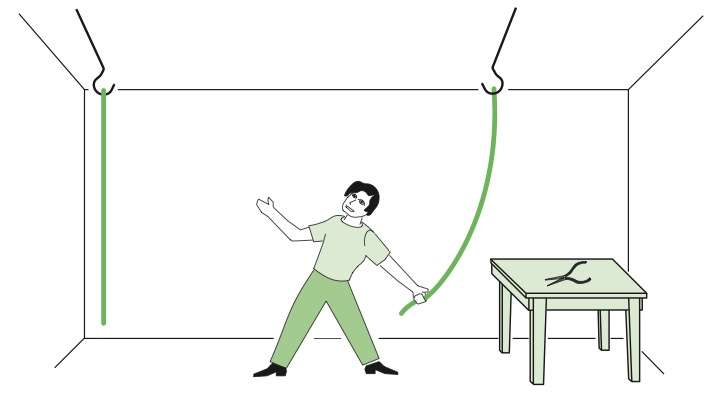

You enter a room in which two strings are hanging from the ceiling and a pair of pliers is lying on a table. Your task is to tie the two strings together. Unfortunately, though, the strings are positioned far enough apart so that you can’t grab one string and hold on to it while reaching for the other. How can you tie them together?

(The answer is below the following picture if you want to take a second and try to figure it out.)

The trick to this problem is to stop thinking about pliers as pliers, and instead to think of it as a weight. (This is sometimes called overcoming functional fixedness.) With that realization in hand, just tie the pliers to one rope and swing it. If you stand by the other rope, the pliers-rope should eventually swing back to you, and then you can tie them together.

In this case, the insight is changing the representation of pliers as tool-to-hold-objects-together to pliers as weight. More support for this view comes from another famous insight problem.

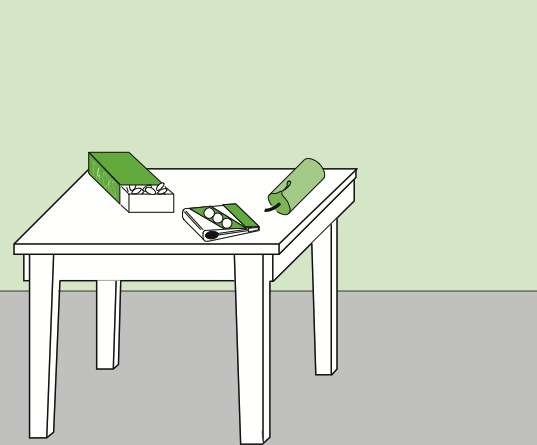

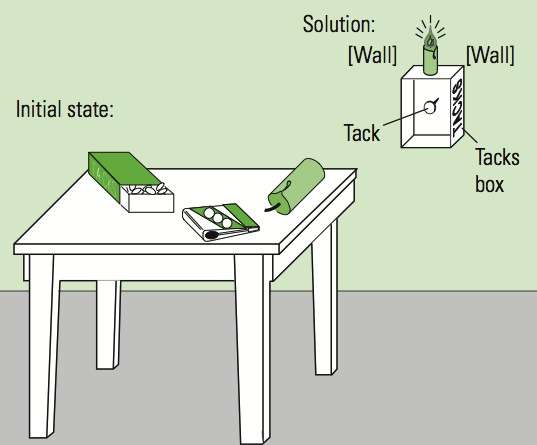

You are given the objects shown: a candle, a book of matches, and a box of tacks. Your task is to find a way to attach the candle to the wall of the room, at eye level, so that it will burn properly and illuminate the room.

The key insight in this problem is that the box that the tacks are contained in is not just for holding tacks, but can be used as a mount, too — again, a change in the representation.

In fact, the rate at which people solve this problem depends on how it’s presented. If you put people in a room with the tacks in the box, they’re less likely to solve it than if the tacks and box are separate.

The way we frame problems makes them more or less difficult. Insight is the spontaneous reframing of a problem. This suggests that we can increase our general problem solving ability by actively thinking of new ways to represent and think about a problem — different points of view. There are a couple of ways to accomplish this. Translating a problem into another medium is a cheap way of producing insight. Often, creating a diagram for a math problem, for example, can be enough to make the solution obvious, but we need not limit ourselves to things we can draw. We can ask ourselves, “How does this feel in the body?” or imagine the problem in terms of a fable.

Further, we can actively retrieve and create analogies. George Pólya in his How to Solve It writes (paraphrased), “You know something like this. What is it?” The history of science, too, is filled with instances of reasoning by analogy. Visualize an atom. What does it look like? If you received an education anything like mine, you think of it as like a solar system, with subatomic particles rotating a nucleus. This is not really what an atom looks like, though, but it has stuck with us by way of Rutherford.

Indeed, we can often gain cheap insights into something by borrowing the machinery from another discipline and thinking about it in those terms. Social interaction, for instance, can be thought of as a market, or as the behavior of electrons that think. We can think of the actions of people in terms of evolutionary drives, as those of a rational agent, and so on.

This perhaps explains some of the ability of some scientists to contribute to different disciplines with original insights. I’m reminded of Feynman’s work on the connection machine, where he analyzes the computer’s behavior with a set of partial differential equations — something natural for a physicist, but strange for a computer science who thinks in discrete rather than continuous terms.

Incubation

We can think of problem solving like a walnut, a metaphor that comes to me by way of Grothendieck. There are two approaches to cracking a walnut. We can, with hammer and chisel, force it open, or we can soak the walnut in water, rubbing it from time to time, but otherwise leaving it alone to soften. With time, the shell becomes flexible and soft and hand pressure alone is enough to open it.

The soaking approach is called incubation. It’s the act of letting a problem simmer in your subconscious while you do something else. I find difficult problems easier to tackle after I’ve left them alone in a while.

The science validates this phenomena. A 2009 meta-analysis found significant interactions between incubation and problem solving performance, with creative problems receiving more of a boost. Going further, they also found that the more time that was spent struggling with the problem, the more effective incubation was.

Sleep

Keep your subconscious starved so it has to work on your problem, so you can sleep peacefully and get the answer in the morning, free.

—Richard Hamming, You and Your Research

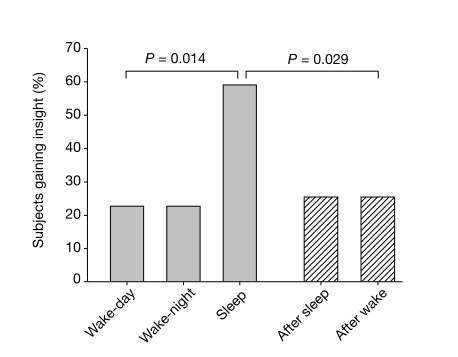

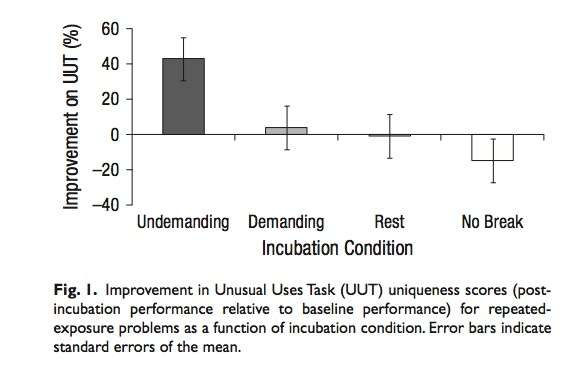

A 2004 study published in Nature examined the role of sleep in the process of generating insight. They found that sleep, regardless of time of day, doubled the number of subjects who came up with the insight solution to a task. (Presented graphically above.) This effect was only evident in those who had struggled with the problem, so it was the unique combination of struggling followed by sleep and not sleep alone that boosted insight.

The authors write, “We conclude that sleep, by restructuring new memory representations, facilitates extraction of explicit knowledge and insightful behaviour.”

The Benefits of Mind Wandering

Individuals with ADHD tend to score higher than neurotypical controls on laboratory measures of creativity. This jives with my experience. I have a cousin with ADHD. He’s a nice guy. He likes to draw. Now, I’ve never broken out a psychological creativity inventory at a family reunion and tested him, but I’d wager he’s more creative than normal controls, too.

There’s a good reason for this: mind-wandering fosters creativity. A 2012 study (results pictured below) found that any sort of mind-wandering will do, but the kind elicited during a low-effort task was more effective than even that of doing nothing.

This, too, is congruent with my experience. How much insight has been produced while taking a shower or mowing the lawn? Paul Dirac, the Nobel Prize winning physicist, would take long hikes in the wood. I’d bet money that this was prime mind-wandering time. I know walking without goal is often a productive intellectual strategy for me. Rich Hickey, known as inventor of the Clojure programming language, has sorta taken the best of both worlds — sleep and mind wandering — and combined them into what he calls hammock driven development.

But how does it work?

As is often the case in the social sciences, there is little consensus on why incubation works. One possible explanation, as illustrated by the Hamming quote, is that the subconscious keeps attacking the problem even when we’re not aware of it. I’ve long operated under this model and I’m somewhat partial to it.

Within cognitive science, a fashionable explanation is that during breaks we abandon approaches that are ineffective. Thus, next time we view a problem, we are prone to try something else. There is something to this, I feel, but some sources go too far when they propose that this is all incubation consists of. I have notice significant qualitative changes to the structure of my own beliefs that occur outside of conscious awareness. Something happens to knowledge when it ripens in the brain and forgetting is not all of that something.

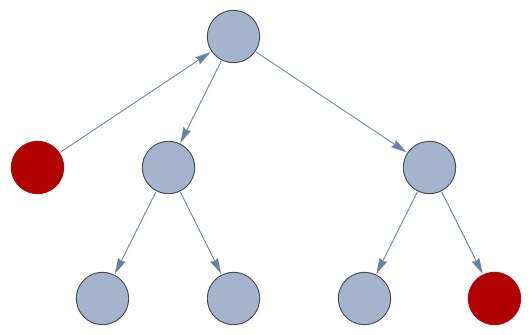

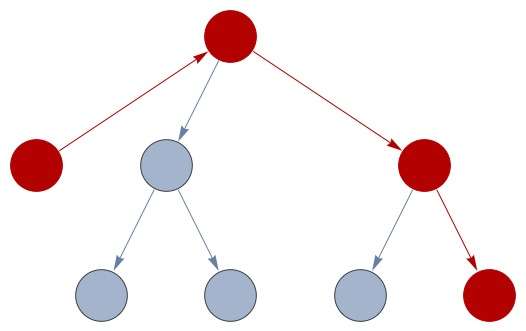

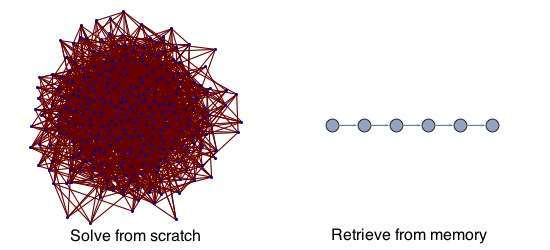

In terms of our initial graph, I have a couple ideas. We still do not have a great grasp on why animals evolved the need to sleep, but it seems to be related to memory consolidation. Also note the dramatic change thought processes undergo while on the edge of sleep and while dreaming. This suggests that there are certain operations, certain nodes in our search graph, that can only be processed and accessed during sleep or rest. Graphically, it might look like:

This could be combined with a search algorithm like tabu search. During search, the mind makes a note of where it gets stuck. It then starts over, but uses this information to inform future search attempts. In this manner, it avoids getting stuck in the same way that it was stuck in the past.

Problem Solving Strategies

It is really a lot of fun to solve problems, isn’t it? Isn’t that what’s interesting in life?

—Frank Offher

There may be no royal road to solving every problem with ease, but that doesn’t mean that we are powerless in the face of life’s challenges. There are things you can do to improve your problem solving ability.

Practice

The most powerful, though somewhat prosaic, method is practice. It’s figuring out the methods that other people use to solve problems and mastering them, adding them to your toolkit. For mathematics, this means mastering broad swathes of the stuff: linear algebra, calculus, topology, and so on. For those in different disciplines, it means mastering different sorts of machinery. Dan Dennet writes about intuition pumps in philosophy, for instance, while a computer scientist might work at complexity theory or algorithmic analysis.

It is, after all, much easier to solve a problem if you know the general way in which such problems are solved. If you can retrieve the method from memory instead of inventing it from scratch, well, that’s a big win. Consider how impossible modern life would be if you had to reinvent everything, all of modern science, electricity, and more. The discovery of calculus took thousands of years. Now, it’s routinely taught to kids in high school. In terms of imagery, we can think of solving a problem from scratch as a complicated graph search, while retrieving a method from memory as a look-up in a hash table. The difference looks something like this:

All of this is to say that it’s very important that you familiarize yourself with the work of others on different problems. It’s cheaper to learn something that someone else already knows than to figure it out on your own. Our brains are just not powerful enough. This is, I think, one of the most powerful arguments for the benefits of broad reading and learning.

Mood

Moods can be thought of as mental lenses, colored sunglasses, that encourage different sorts of processing. A “down” mood encourages focus on detail, while an “up” mood encourages focusing on the greater whole.

Indeed, multiple meta-analyses suggests that those in happier moods are more creative. If you’ve ever met someone who is bipolar, you’ll notice that their manic episodes tend to look a lot like the processing of creative individuals. As someone once told me of his manic episodes, “There’s no drug that can get you as high as believing you’re Jesus Christ.”

This suggests that one ought to think about a problem while in different moods. To become happy, try dancing. To be sad, listen to sad music or watch a sad film. Think about the problem while laughing at stand-up comedy. Discuss it over coffee with a friend. Think about it while fighting, while angry at the world. The more varied states that you are in while considering your problem, the higher the odds you will stumble on a new insight.

Rubber Ducking

Rubber ducking is a technique for debugging that’s famous in the programming community. The idea is that simply explaining your problem to another person is often enough to lead to the eureka! In fact, the theory goes, you don’t even need to describe it to another person. It’s enough to tell it to a rubber duck.

I have noticed this a number of times. I’ll go to write up something I don’t understand, some problem I have on StackOverflow, and then bam, the answer will punch me in the face. There is something about describing something to someone else that solidifies understanding. Why do you think I’m going through the trouble of writing all of this up, after all?

The actual science is a bit mixed. In one study, describing current efforts on a problem reduced the likelihood that one would solve the problem. The theory goes that this forces one to focus on easy-to-verbalize parts of the problem, which may be irrelevant, and thus entrenches the bad approach.

In a different study, though, forcing students to learn something well enough to explain to another person increased their future performance on similar problems. A number of people have remarked that they never really understood something until they had to teach it, and this maybe explains some of the success of the researchers-as-teachers paradigm we see in the university system.

Even with the mixed research, I’m confident that the technique works, based on my own experience. If you’re stuck, try describing the problem to someone else in terms they can understand. Blogging works well for this.

Putting it All Together

In short, then:

- Problem solving can be thought of as search on a graph. You start in some state and try to find your way to the solution state.

- Insight is distinguished by a change in problem representation.

- Insight can be facilitated by active seeking of new problem representations, for example via drawing or creating analogies.

- Taking breaks during working on a problem solving is called incubation. Incubation enhances problem solving ability.

- A night’s sleep improves problem solving ability to a considerable degree. This may be related to memory consolidation during sleep.

- Mind-wandering facilitates creativity. Low effort tasks are a potent means of encouraging mind-wandering.

- To improve problem solving, one should study solved problems, attack the problem while in different moods, and try explaining the problem to others.