The Secretary Problem Explained: Dating Mathematically

I was, to put it mildly, something of a mess after my last relationship imploded. I wrote poems and love letters and responded to all of her text messages with two messages and all sorts of other things that make me cringe now and oh god what was I thinking.

I learned a few things, though, like when you tell strangers that your long-term relationship has just been bulldozed as thoroughly as the Romans salted Carthage, they do this sorta Vulcan mind-meld and become super empathy machines. Even older folk, who usually treat me not exactly as a non-person but something sorta like it. At the time, I had this gruff, Russian psychiatrist I’d see once a month, and he was all like, “Been there, man. Have some Diazepam and relax.” — except, you know, he said it in Russian-accented doctorspeak.

This was surprising to me then but isn’t now. Live long enough and you’ll have your heart thrashed about a fair bit, along with the rest of you. Mention heartbreak and everyone has their own private story — maybe more than one. It’s not Vietnam. They’ve been there and they understand.

I sometimes wonder — if I could go back in time, what could I say to comfort my former self? What can you say to someone that will pull them out of the throes of hormone-induced suffering? Probably nothing. The remarkable thing about words is not that they sometimes move people, but that they so seldom do.

Still, I think I’d say something like, “My boy, evolution is a motherfucker and you need a new woman in your life.” He would probably protest that women were the problem and that he’s pretty sure the last thing he needs is another one. Then, I would let out the most condescending sigh imaginable, the sort of sigh that says I-have-unimaginable-wisdom-born-of-experience-and-am-from-the-future, and say, “Not that sort of woman. You need the Queen. You need mathematics –”

“Let me tell you about the secretary problem.”

The Secretary Problem

Consider the plight of John. John’s 25. He lives in Utah and likes country music, hunting, and four wheelers. You probably see where I’m going with this. That’s right, ladies and gentlemen. John is gay.

The recent supreme court decision overturning gay marriage in Utah has him thinking. He’d like to settle down one day — maybe adopt a child with the right man. He has a couple short-term relationships going on right now, but married to Bruce or Sidney? No way.

How can he guarantee that he snags, if not Mr. Right, at least Mr. Close Enough? He figures he ought to date at least a few different men, and then… what?

Imagine he meets this guy, Jim. They make out at a party, hang out a few times, and realize that they’re kinda already dating, and decide to label it by making it Facebook official. Things progress. John asks Jim to move in with him.

Then there’s a snag. Valentine’s Day rolls around, and John finds himself, at the last minute, at Walmart, looking to pick up some chocolate and cheap Champagne, wondering, “Is this really what love feels like?”

What should John do in such a situation? Should he next Jim and take his chances on the dating market? Or should he settle and settle down?

John’s predicament is an example of the secretary problem — so named because we can imagine the same situation, except instead of a man searching for a husband, it’s a man interviewing potential secretaries. When is the candidate good enough? What’s the stopping criteria?

Formalizing the Secretary Problem

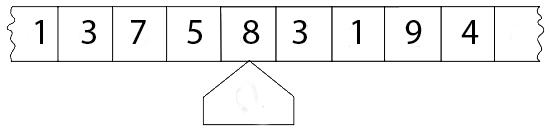

We can abstract away the specifics of John’s plight and formalize the problem. Let’s consider each man that John dates as an integer — the integer representing his “husbandness factor.” Thus, a sequence of lovers like \((Sidney, Bruce, Jim, Todd, Keith, Bruno, Terrence, Cecil, Nigel)\) would translate to the integer sequence \((1, 3, 7, 5, 8, 3, 1, 9, 4)\).

This problem would be trivial — just pick the max element — if it weren’t for two properties.

- There’s no look-ahead. When I’m dating any one person, I’m unable to look forward into the future and consider who I’ll date in the future. I have no crystal ball.

- There’s no undo. If I date a great girl for a while, but leave her in a misguided attempt to find someone better, there’s a good chance she’ll be unavailable in the future, married to some douche named Trevor who played lacrosse in high school.

We can think of it visually as a machine which is fed a tape of integers. It has two actions: it can either stop or it can consider the next integer. The machine’s objective is to stop on the highest integer.

Real World Examples of the Secretary Problem

At the heart of the secretary problem is conflict. Do I reject the current possibility in hopes of landing something better if I keep looking, or do I stick with what I have?

Examples of the secretary problem:

- This is the case with dating. I could commit to the woman I’m with right now or I could start texting her best friend.

- It applies to hiring not just secretaries, but anyone. Is the current candidate the right person for the job or should I hold out for someone better? What if no one comes along?

- When buying a house — should I put an offer on some house, or should I hope that something better comes along in the future? How many houses ought I look at before deciding?

- The opposite side of the interviewing problem: should I accept this job offer or should I keep looking?

- Alligator hunting, at least in Louisiana. Each year, you’re allotted a set number of tags based on the size of your property — that’s the amount of alligators you’re allowed to “harvest” under the law. When you stumble across an alligator, you’re forced to decide: should I kill this one or save my tag and hope a bigger one comes along?

- When selling a house or a car or, well, any big ticket item. When presented with an offer, you’re forced to decide: should I accept this offer or hope something better comes along?

- Deciding whether or not to buy something at the supermarket. Is this bread cheap enough or should I hope for a sale next week? The same goes for clothing and, well, anything.

Solving the Secretary Problem

The following contains the formal details for solving the secretary problem analytically. It can safely be skimmed.

As a general problem solving strategy, I often find it useful to first come up with a horrible solution to a problem and then iterate from there. I call this the dumbest-thing-that-could-work heuristic.

In the case of the secretary problem, our horrible solution can be the lucky number seven rule: In an integer sequence, always choose the 7th item.

If we follow this rule, we’re essentially picking an integer at random. The probability, then, of picking the best element from an integer sequence of length \(N\) with this rule is \(\frac{1}{N}\).

To beat this, let’s consider how people go about solving secretary problems in the real world. I don’t know anyone who’s dating strategy is, “I’m going to date seven women and pick the seventh one — no matter what.” One would have to be a staunch nihilist to adopt such a strategy.

Instead, the strategy most adults adopt — insofar as they consciously adopt a strategy — is to date around for a while, gain some experience, figure out one’s options, and then choose the next best thing that comes around.

In terms of the secretary problem, such a strategy would be: Scan through the first \( r \) integers and then choose the first option that is greater than any of the integers in \( [1,r] \).

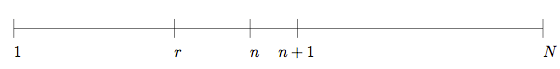

How does this new strategy compare to our old one? The above image is a prop to help understand the discussion that follows. Assume that \(i\), the greatest integer, occurs at \(n + 1\).

In order for this strategy to return the maximum integer, two conditions must hold:

The maximum integer cannot be contained in \([1,r]\). Our strategy is to scan through \([1,r]\), so if the solution is in \([1,r]\), we necessarily

lose. This can also be stated as \(n \geq r\).

Our strategy is going to select the first integer, \( i \), in \([r,N]\) that’s greater than \(max([1,r])\). Given this, there cannot be any integers greater than \(i\) that come after \(i\), otherwise the strategy will lose. Alternatively put, the condition \(max([1,r]) == max([1,n])\) must be true.

Thus, to calculate the effectiveness of our strategy, we need to know the

probability that both of these will hold. For some given \(n\), this is:

$$ \frac{r}{n}\frac{1}{N} $$

\(\frac{1}{N}\) is the probability that \(i\) occurs at \(n + 1\) (remember, this is the probability for some n, not the n), while \(\frac{r}{n}\) is a consequence of the second condition — the probability that the condition \(max([1,r]) == max([1,n])\) is true.

To calculate the probability for some \(r\), \(P®\), not for arbitrary \(n\), but for everything, we need to sum over \(n \geq r\):

$$ P® = \frac{1}{N}(\frac{r}{r}+\frac{r}{r+1}+\frac{r}{r+2}+…+\frac{r}{N-1}) = \frac{r}{N}\sum_{n=r}^{N-1}\frac{1}{n} $$

This is a Riemann approximation of an integral so we can rewrite it. By letting \(\lim_{N \rightarrow \infty}\frac{r}{N} = x\) and \(\lim_{N \rightarrow \infty}\frac{n}{N} = t\), we get:

$$ P® = \lim_{N \rightarrow \infty}\frac{r}{N}\sum_{n=r}^{N-1}\frac{N}{n}\frac{1}{N}=x\int_{x}^{1}\frac{1}{t}dt=-x \ln x $$

Now, we can find the optimal \(r\) by solving for \(P’® = 0\). By plugging \(r_{optimal}\) back into \(P®\), we will find the probability of success.

$$ P’® = -\ln x – 1 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{1}{e} $$

$$ P(\frac{1}{e}) = \frac{1}{e} \approx .37 $$

What The Math Says

How can this math help John? Well, the optimal solution is for him to estimate how many people he believes he might reasonably date in the future, say \(20\). We plug this into the equation \(\frac{N}{e}\), where \(N=20\), \(\frac{20}{e} \approx 7\).

This result says that, if John wants to maximize his probability of ending up with the best possible man, he should date 7 men and, then, marry the next man who is better than all of those men.

However, we have sneaked some probably untenable assumptions into our analysis. The typical secretary problem maximizes the chances of landing the best man, and considers all other outcomes equally bad. Most on the dating market are not thinking this way — they want to maximize the probability that they end up with a pretty good spouse. It’s not all or nothing.

Maximizing the Probability of a Good Outcome

Fear not, there’s a modification of the secretary problem that maximizes the probability of finding a high-value husband or wife. I’m not going to cover the derivation for this flavor of the secretary problem in this post. (For technical details, see Bearden 2005), but suffice it to say, the strategy is the same except we use a cutoff of \(\sqrt{N}\) rather than \(\frac{N}{e}\).

Consider dating for the average American. Assuming one wants to settle down by the age of 35, one has the opportunity for somewhere between 7 and 30 sorta serious relationships. Taking the geometric mean, we get about 14. Johannes Kepler famously considered 11 women for his second wife, so this is, at the very least, not absurd.

The square root of 14 is about 4. Thus, according to the math, one should have four kinda serious relationships and then marry the next person that comes along who is better than all of those four.

How Human Behavior Compares to the Mathematics

The median number of premarital sexual partners is unclear, with different sources reporting markedly different numbers. I’m inclined to place the number between 1 and 4. Using this number as a rough proxy for the number of kinda serious relationships before marriage, reality conflicts with the results of the secretary problem.

Most people aren’t dating even four other people before marriage. What gives?

At its core, the conflict implies that either the solution to the secretary problem does not apply or that humans are not gathering enough information before getting married.

A number of experimental studies (here, here, here, and here) support the second view. When undergraduates are asked to participate in a secretary problem in its pure form — that is, like the tape discussed in the beginning — they almost always stop searching too early.

One might argue that evolution ought to know what it’s doing — especially when it comes to human mating — and that we should have a strong prior that dating is, in some sense, optimal. Such a view ignores that we’re no longer in small tribes of 50 to 200. Humans did not evolve to deal with modern society and the horror that is dating today. A preference for sugar was adaptive 50,000 years ago, but we have since invented the Twinkie.

Indeed, probably pre-civilized human life didn’t look a whole lot like a secretary problem. Back then, one might have had to choose from a half dozen possible mates — mates one had already known for many years. This looks more like a game of pick the maximal element from a set than a bona fide secretary problem.

What Sort of Optimal?

If I use the results of the secretary problem to find a wife, I will almost certainly end up worse off than a strictly rational agent who pursues the same goal, but probably better than those who have no strategy at all. At the end of the day, the secretary problem is a mathematical abstraction and fails to take into account much of complexity of, you know, reality.

The secretary problem assumes, for instance, that our only means of finding out about the distribution of potential mates and our preferences for them is via dating. This isn’t remotely true. We can observe the actions of others, introspect, read about human mate preferences, discuss our experiences with friends, and otherwise share information.

It’s also not the case that we’re dating men or women at random. There are a huge number of filters that go into deciding whether or not someone is marriage material. Are we of similar ages and interests? Do we speak the same language? Do I feel any attraction for this person?

A theory of optimal dating would need to take this and much more into account. There are a near unlimited number of paths to strategically choosing who to spend the rest of your life with, and a lot of that strategy consists of things other than choosing. You might try getting fit, earning more money, adopting interesting hobbies, honing social skills, meeting lots of the opposite sex, taking voice acting or improv classes, and so on. An optimal theory of dating would, I have no doubt, emphasize some subset of these skills.

All Together Now

- The secretary problem is the problem of deciding whether or not one should stick with what they have or take their chances on something new.

- Examples of secretary problems include finding a husband or wife, hiring a secretary, and alligator hunting.

- The solution to the secretary problem suggests that the optimal dating strategy is to estimate the maximum number of people you’re willing to date, \(N\), and then date \(\sqrt{N}\) people and marry the next person who is better than all of those.

- In laboratory experiments, people often stop searching too soon when solving secretary problems. This suggests that the average person doesn’t date enough people prior to marriage.

- At the end of the day, the secretary problem is a mathematical abstraction and there is more to finding the “right” person than dating a certain number of people.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia has a page on the secretary problem.

- For some history of the secretary problem, see the paper, “Who solved the secretary problem?”

- For more details on the problem and its variants, see the paper “The Secretary Problem and Its Extensions: A Review.”

- For resources on how to solve the secretary problem, there’s this paper and this introduction.

- On making the leap from the lucky number seven rule to the optimal solution, there’s some discussion on the math StackExchange.

- This article was inspired by a recent blog post by a mathematician on using the secretary problem to find a house. Discussion here.