What Makes Something Interesting?

Francis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin and maybe best known for his work on intelligence, was a bit obsessed with the idea that people have certain innate traits. You know the movie Minority Report, where a special police department tries to predict crime before it happens? He sorta tried to invent it — in 1883.

He had this idea, see, that you could predict whether or not someone was a criminal based on the structure of their face. He devised a technique of composite photography, which allowed him to create averages of many images. While he didn’t manage to identify criminals, he did find that the average of several faces tended to be more attractive than any of the individual faces he used as input.

More than 100 years later, it turns out Galton was on to something — regarding both crime and attractiveness. Men with wider faces are more aggressive hockey players, less trustworthy in laboratory games, engage in more aggressive behavior, and are more successful CEOs. Computer averages of faces are more attractive than the people used as inputs, and this result holds not only for faces, but for averages of cars, fish, and birds. A wide face is a dangerous face and an average fish is an attractive fish, it seems.

The Beautiful is the Compressible

We can think of human beings as agents who take in information from the environment, run that information through a compressor module, and then store that information in long-term memory. This is not rocket science. Our brains can’t hold all of the information in the world. We forget. We are forced to compress experience down to a few relevant details and store those. Indeed, a fair amount of evidence now supports the hypothesis that memories are reconstructed during recall. Each time you remember something, you’re modifying that memory. The brain is not a high-fidelity recorder.

In our man-as-compressor model, what sets the beautiful, averaged face apart from a typical face? It’s easier to compress. Consider all the information the brain has to store about a hideous face: a giant nose, a lazy eye, a unibrow, scars, maybe a teardrop tattoo. When the brain encounters a beautiful face, though, the compressor says something like, “Ah, a face so face-like that I need not spend any more processing time on it. I can relax.”

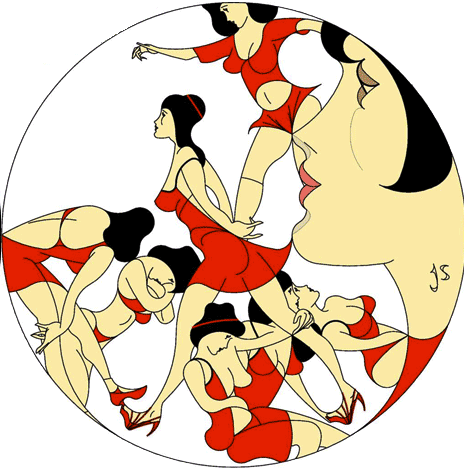

This idea is taken to its logical extension in low-complexity art. The aim of low-complexity art is to create images that can be described by a short computer program — a measure of complexity known as Kolmogorov complexity. The picture at the beginning of this section is an example of this style of art.

The Interesting is the Unexpected

Consider two facts:

- Men commit 90% of violent crime.

- The size of the human brain has decreased 10% over the past 20,000 years.

When I speak to people, they find the second fact a lot more interesting than the first. This is, I think, because it violates their model of the world. They think of evolution as pushing us toward ever increasing complexity, but this is not true. Consider venereal sarcoma, which is today an infectious cancer, but used to be a dog.

This notion of surprise, the violation of expectation, is at the core of interestingness. If you already know something, if you anticipated it, it’s boring. The first time you hear a joke, it’s funny. The second time, not so much.

But not all unexpected data is interesting. If I published random sequences of numbers instead of words on this blog, well, no one would read it, and I wouldn’t blame them. What separates the interesting from the uninteresting?

If we consider our man-as-compressor model, interesting facts are those that improve the future performance of the compressor. Here’s an example: marriages are more likely to dissolve during periods of unemployment, but this only holds for unemployed husbands. For someone unaware of this fact, it improves their compressor — in this case, predicting when a couple will get divorced. (If you can predict something, you can compress it. They’re the same construct.) Depending on the person, this fact might further propagate through their compressor, updating beliefs about human mate preferences.

Indeed, a discovery is “just” a large improvement in the compressor. Consider Darwin’s theory of evolution. It connects and explains a huge amount of the phenomena around us. Where did humans come from? Why do fats taste good? Why do whales have organs similar to those of humans — and not fish? Talk about a compression upgrade.

We can even tie this into curiosity. After all, what is curiosity if not the pursuit of one’s interests? Given that what is interesting are those things that upgrade our model of the world, curiosity can be thought of as a drive to improve the compressor — a drive to improve our understanding of how things work.

Creativity, too, can be understood through the compressor model. Creativity is the consistent violation of other people’s expectations. Consider this poem:

Roses are red,

And ready for plucking,

You’re sixteen,

And ready for high school.

—Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions

Notice how it violates the expectations of the compressor? That’s creativity.

All together, then:

- Humans can be thought of as agents who take in information from the environment, run it through a compressor, and store the result in long-term memory.

- Something is beautiful insofar as it can be compressed. Example: an average of faces is more beautiful than any individual face.

- How interesting something is depends on how much it improves the performance of the compressor. When a fact violates expectations and improves one’s model of the world, that’s interesting. It improves the compressor.

- Curiosity is the pursuit of the interesting — action designed to improve the compressor.

- Creativity is the consistent violation of the expectations of the compressor.

Further Reading

- Another introduction to these ideas can be found here.

- I’ve written a little about simplicity, mathematics, and art before.

- Here’s an introduction to low-complexity art.

- Here are a two more overviews of the theory: here and here.