Why Category Theory Matters

I hope most mathematicians continue to fear and despise category theory, so I can continue to maintain a certain advantage over them.

—John Baez

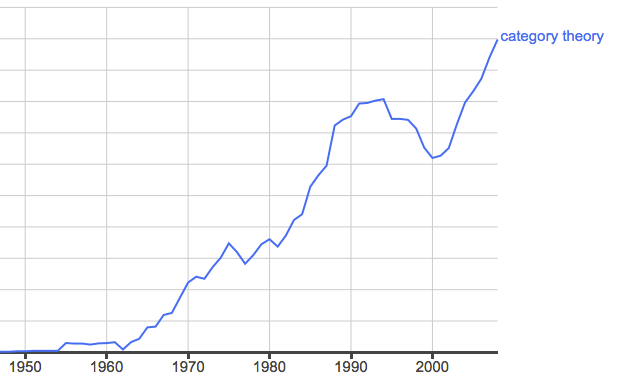

The above is a graph of the number of times the phrase “category theory” has been used in books, from about 1950 through the present. It speaks for itself.

But why? What’s the big deal? Why does category theory matter? I’m about a quarter of the way through Conceptual Mathematics: A First Introduction to Categories and still not sure why I’m bothering with fleshing out all this theory. Is this just set theory for hipsters?

What category theory is about

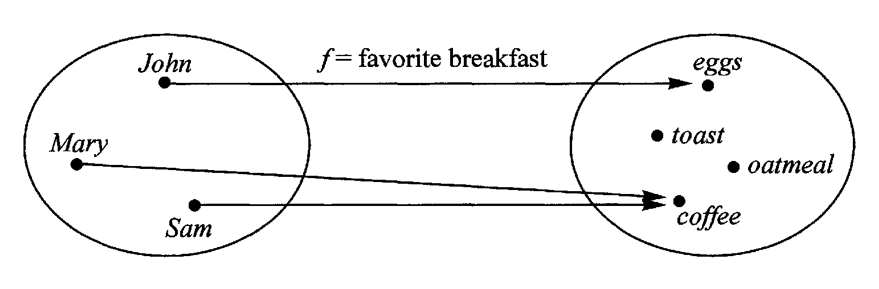

Category theory is, essentially, the study of mathematical structure. It’s the study of things and the mappings between those things, the translations of these objects. These are usually called objects and morphisms (or arrows, if you prefer). Objects can be thought of as sets and arrows as functions, though they are not limited to this interpretation.

The subject’s major insight is, in order to understand something, focus on the structure preserving mappings of that something — the legal translations.

What the excitement is about

The vast applicability and expressiveness of category theory leads to the observation that most structures in mathematics are best understood from a category theoretic or higher category theoretic viewpoint.

—nLab

Category theory is one of, if not the most, abstract fields of mathematics. It’s even been dubbed, as one might tease a younger sibling, “abstract nonsense.” After all, the field throws out all the specific properties of objects and instead focuses solely on their translations.

This extreme generality of category theory means that it can say something about anything, but nothing too specific. In other words, part of the growth of category is probably because you can use it to talk about damn near anything. (See the applications below for examples.)

In this respect, category theory is like set theory. The popularity of set theory is a result of the fact that, hey, it’s a pretty good language for talking about a lot of different types of mathematics. Most things can be formalized as a combination of sets and first order logic, and it’s not that unnatural to think in terms of sets so, bam, popularity.

In Categories for Software Engineering, the authors put it this way: “The way we like to present category theory is as a toolbox similar to set theory: as a kind of mathematical lingua franca in the sense that it can be used for formalizing concepts that arise in our day-to-day activity.”

This generality mirrors the difference between strong and weak methods in artificial intelligence. General methods, while widely applicable, don’t typically scale up to hard problems. Instead, specialized tools are necessary. In the same way, category theory is more of a tool for elucidating connections between mathematical structures than for solving problems — in contrast with something like linear algebra, or really any field of applied math.

Benefits of category theory over set theory

God made the integers, all the rest is the work of man.

—Leopold Kronecker

To be honest, I don’t like set theory. It’s artificial — the axioms aren’t obviously true, but rather the product of a search for a paradox-free foundation for mathematics. It’s sort of complicated, maybe not at the lowest levels, but definitely once you try to build up something like the real numbers. (A 2008 issue of the AMS reports, “…to expand the definition of the number 1 fully in terms of Bourbaki primitives requires over 4 trillion symbols.”)

The whole enterprise is bizarre. As humans, we didn’t start out with sets and then build out mathematics. No, the Egyptians did arithmetic and some algebra. (The oldest extant mathematical records deal with the Pythagorean theorem.) Animals have some notion of magnitude and many can even count. Set theory, rather than a natural extension of mathematical enterprise, seems more like something forced — the difference between English and Esperanto.

As far as I can tell, the mathematical community agrees with me. Paul Cohen is the only person to ever win a Fields medal for work on foundations and today “foundations of mathematics” is code not for mathematics, but philosophy.

So, immediately, category theory has an advantage over set theory in that it’s a less artificial construction, given that it stems directly from work in algebraic topology.

But, beyond that, is their anything else exciting about category theory? The main draw is its ability to connect otherwise disparate fields, a sort of skeleton to hang other knowledge on. Mike Stay and John Baez write about this in their “Physics, topology, logic and computation: a Rosetta Stone”, where they use category theoretic constructs to speak about the similarities between — you guessed it — physics, topology, logic, and computation.

Jocelyn Ireson-Paine puts it this way, “category theory is a great source of unifying concepts and organizing principles.” This is the benefit of all the abstraction — by throwing away all the details, an object’s structure reveals itself.

As a concrete example, consider one of the most profound mathematical achievements, Descartes’s discovery of analytic geometry — the realization that geometry can be translated into cartesian coordinates and, thus, the power of algebra can be brought to bear on the subject.

With category theory, this discovery can be expressed in what has to be one of the most satisfying formulas of all time:

\( P \xrightarrow{\quad f \quad} \mathbb{R}^{2} \)

Applications of category theory

The above is nice and all, but it’s still just sort of hey-take-my-word-for-it, which is not so satisfying. Here are some actual examples:

- Category theory has been used to study grammar and human language.

- In building a spreadsheet application.

- As a descriptive tool in neuroscience.

- In the analysis and design of cognitive neural network architectures.

- Many applications in graduate level mathematics (i.e. stuff I don’t understand) and physics.

- In programming languages, especially Haskell and most famously monads, but also, for instance, a typed assembly language and work on the typed lambda calculus.

- Generating program optimizations.

- To model systems of interacting agents.

- To generalize sorting algorithms.

- To understand collaborative text editing.

- To understand optimal play in sequential games like chess.

- To formalize the notion of algorithm.

- In the study of analogy.

- As “a language for experimental design patterns” and “a new vocabulary in which to think and communicate.”

- In definitions of emergence and discussions of biology.

- Generally speaking, there seems to be a cabal of radical category theorists, led by John Baez, who are reinterpreting anything interesting in category theoretic terms. (The trend reminds me of reinventing the wheel for the nth time in the nth newest programming language.)

I will leave you with the following:

[Category theory] does not itself solve hard problems in topology or algebra. It clears away tangled multitudes of individually trivial problems. It puts the hard problems in clear relief and makes their solution possible.

Further Reading

- If you enjoyed this, you might enjoy some of my other posts on math, including one on the secretary problem, the stable marriage problem, mathematical proof, and worldbuilding and mathematics.

- There are several free online category theory texts, including Abstract and Concrete Categories – The Joy of Cats and Category Theory for Scientists.

- There’s often interesting category theoretic discussion at the n-Category Cafe.

- The “Catsters” have a series of online videos about category theory.