Worldbuilding, Worldbuilders, and Mathematics

This week, I was introduced to the hobby of worldbuilding — inventing imaginary places, making maps, elaborating histories. (The platonist in me prefers to think of worldbuilding as the discovery of fictional universes, rather than an act of invention.)

Tolkien

There is a (perhaps apocryphal) tale that J. R. R. Tolkien got into a fight with his publisher over using the words “elves” and “dwarves” instead of “elfs” and “dwarfs”. The publisher argued that the latter was how the dictionary did it. “I know,” Tolkien responded, “I wrote the dictionary.” Tolkien had, in fact, spent several years as an assistant working on the Oxford English Dictionary.

Although most known for his fiction, Tolkien was a linguist at heart, even inventing some eleven fictional languages along with a number of variations on those languages.

The remarkable degree of internal consistency of some Tolkien’s language use in The Lord of the Rings is perhaps unsurprising, then. The prefix “mor” in his work translates literally to black and is used consistently — Mordor is black land, moria is black pit, and morranon is black gate. The “dor” in Mordor means land. Gondor, as you might expect, means stone land.

Of his languages and Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wrote “The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.”

Foundations

It’s very far away,

It takes about half a day

to get there

if we travel by my, uh, dragonfly.

—Jimi Hendrix, “Spanish Castle Magic”

I have no such patience for languages. I have little interesting in learning a new one, except perhaps Lojban, and less still in attempting to invent my own, unless we’re speaking of programming.

But it does suggest a question: Where would I start with discovering a fictional universe? If I wanted to maximize the believability of a fictional universe, on what rock would I put it?

I’m thinking maybe economics. Robin Hanson recently pointed out that the movie Her, while enjoyable, is far from realistic. Humans invent human-level “strong” AI and use it… to chat with.

I doubt that’s how it’s going to play out in the real world. Why bother hiring a human to do any sort of computer work when an AI can do it faster, better, and cheaper? Newspaper reporter? Computer has it covered. Secretary? Computer. Author? Computer. Researcher? Computer. Teacher? Computer. Customer support? Computer.

Talk about a fuck up. In the real world, everything makes a perverted sort of sense. A causes B causes C, ad infinitum. In the real world, physics makes the rules, and we, well, we’re an expression of them. When worldbuilding, there is no physics ensuring that what you write is consistent. It’s up to you.

Discovering a coherent world draws on the same skills that are necessary for understanding our own world. When the movie Gravity was released, it was criticized for fucking up a whole lot of physics — vehicles in impossible orbits, backpacks with unlimited fuel supplies, and indestructible space suits.

That’s all ignoring messy details like relationship mechanics, attraction, and how language works. The movie Ted drives me up the wall — not because there is a magical, talking teddy bear, but because Mark Wahlburg and Mila Kunis’s relationship strikes me as absurd. A chick like that, decent career, and she’s with this unemployed man-child? Ri-ght.

All of which is to suggest that the skills and knowledge necessary to understand this world are the same needed to build your own: economics, game theory, physics, social dynamics, and so on. The converse is true, too: to understand this world, consider the sort of things you’d need to know to build your own. Or, as Feynman put it, “What I cannot create, I do not understand.”

The Fractal Nature of Worldbuilding

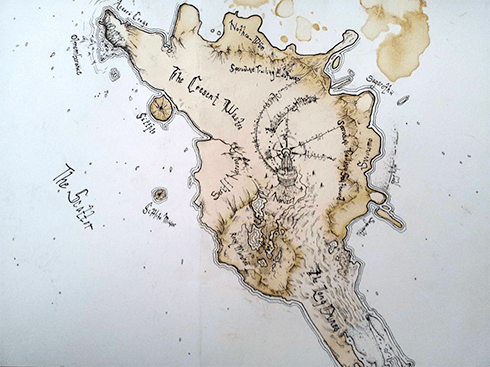

Worldbuilders often go out of their way to produce natural looking maps — like by spilling coffee on paper. Here’s an example:

Another technique for generating maps: taking pictures of rusted fire hydrants.

But there’s a whole branch of mathematics for this sorta thing, fractals! Ever notice the self-similar nature of trees? Each branch looks like a small tree unto itself. Or coastlines — each “crevice” of a coastline itself looks like a coastline. Branches, snowflakes, crystals — all like this.

Indeed, ever after reading Benoit Mandelbrot’s The Fractal Geometry of Nature, I sometimes catch myself seeing fractals superimposed on clouds when I unfocus my eyes.

Mathematics and Worldbuilding

Okay, confession: I wasn’t 100% honest with you. While this is my first brush with groups of other worldbuilders, I’ve toyed with the idea in the past — after colliding with Tegmark’s mathematical universe hypothesis and reading Permutation City.

I wasn’t thinking about making maps. I was wondering: How could I model the essentials of emergent behavior? Is it Conway’s game of life — or something simpler? How could I simulate a universe? What do the fundamental laws of our universe look like?

And I started wondering if mathematics wasn’t a sort of world unto itself. A set of axioms with implications of the sort we could never anticipate — implications we are still discovering, who knows what it could lead to? And not one system of axioms, but infinitely many — each with different definitions, objects, theorems, branches, and applications.

In short, I started to think of the work of a mathematician as being a whole lot like worldbuilding. Discovering some object that obeys certain rules of logic and nothing more, and asking, “What does it do? Is such and such true of this thing? How does it behave here?”

I’m reminded of János Bolyai. Of non-euclidean geometry, he wrote, “Out of nothing I have created a strange new universe.”